Protein, protein, protein. Everyone is eating and talking about getting more of this once humble and unassuming macronutrient. As a naturopathic doctor who has been preaching about the importance of protein for my patients’ mental and hormonal health for 10 years, I’m pleased, kind of. Because, as expected, Big Food has heard this cry for more protein. We now have protein bread, pasta, pancake mix, and cereal. Influencers intensely urge us to follow their top protein hacks. Debates ensue about whether we’re eating too much protein, the risks of eating too much protein, and whether it’s better to consume plant or animal protein.

You don’t need that much protein!

You need more protein!

Certain types of protein aren’t good for you!

You’re destroying the climate/kidneys/your soul with all that protein!

And then, there’s Vanity Fair, which released an article titled “Why Are Americans So Obsessed with Protein? Blame MAGA” (Weir, 2025).

For those who have had the privilege to avoid the particular algorithms that thrust you into the fray of the culture wars, MAGA stands for “Make America Great Again,” and is a nod to the American right, under Donald Trump.

The article argues that those obsessed with protein are chest-beating, ultra-right-wing, macho conservative bros. These men gaze in the mirror while lifting weights and listening to podcasts that discuss selfish masculine man stuff and muscle gains. They pursue physical strength on their way to world domination–they love protein because they love themselves.

This isn’t the first time lifestyle choices have been made political. Another article, published in Rolling Stone, blamed the right for ignoring the sound advice of decades of nutrition recommendations, and avoiding “seed” oils (I like to call them Industrial Oils), in an article titled, quite literally, “Why is the Right So Obsessed with Seed Oils?” (Dickson & Dickson, 2023). After all, Harvard and the American Heart Association have touted seed oils as heart-healthy and better for you than butter (which will kill you) (Zhang et al., 2025). So, if you’re going to ignore this sound, prestigious advice, you must be a right-wing, tinfoil hat-wearing conspiracy nut. Come on, trust the experts, bro.

I find this rhetoric fascinating because it wasn’t too long ago when watching your diet, working out, and eating clean were associated with free-loving hippies. At least up until the early 2000s (perhaps before the culture wars got going), complementary and alternative medicine was mainly embraced by those on the left: cultural creatives, environmentalists, feminists, and other individuals committed to self-expression and self-actualization (Valtonen et al., 2023).

However, we do see a particular health and wellness movement rise from what seems to be the political right. We have the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement, a branch of MAGA, led by figures such as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Dr. Casey Means, which is connected to the Trump administration. It appears that more conservatives are skeptical of conventional health narratives and moving towards alternative health and wellness lifestyle practices, such as mindful dietary choices, solutions beyond pharmaceuticals, and pursuing health knowledge as personal empowerment.

So, how did this come to be? Is the health and wellness industry somehow leaning right?

Like many, I noticed this divide during the COVID era. During the pandemic, expressing skepticism about lockdowns, vaccines, or mask mandates quickly got you branded as “anti-science” or a conspiracy theorist. “Trust the experts,” we were told. Those who asked for evidence about the effectiveness of measures like social distancing, lockdowns, testing practices, mandatory masking, vaccine mandates, accuracy of testing methods, and natural immunity were branded right-wing extremists and conspiracy nuts. If you asked questions, you lacked compassion. You were a danger to society.

The truth was, however, that even the experts warned against lockdown groupthink, with many sound minds arguing for focused protection (Joffe, 2021). An extensive review by the prestigious Cochrane Group, including 11 randomized controlled trials and over 600,000 participants, found no clear benefit to using masks to prevent infection from viral respiratory infections (Jefferson et al., 2023). Pfizer’s very own trial on the mRNA immunizations did not test for transmission, rendering the entire premise of vaccine mandates moot (Polack et al., 2020). Those in the preventive health space noticed that public health officials largely ignored metabolic health and vitamin D deficiency, which were significant risk factors for disease severity (Shah et al., 2022; Stefan et al., 2021). Many health professionals were accused of putting people at risk for pointing out the collateral damage they were witnessing: mental health crises, mistrust of public health institutions, and economic devastation impacting the most vulnerable, which public narratives largely minimized or outright ignored.

The accusation that only one side of the political aisle “believes in science” is itself unscientific, as science is not a religion but a process of inquiry that adapts in the light of new evidence. Science is the pathway through which knowledge and conventional wisdom evolve. And therefore, it is scientific to push against familiar narratives, particularly when they fail to reflect our experienced reality.

Interestingly, the data shows that it is not the right/left divide that predicts health choices (Valtonen et al., 2023). It is not whether you are conservative or liberal that dictates your health beliefs and behaviours, but how much you align with anti-elitism, anti-establishment, and anti-corruption beliefs. Valtonen et al. found that Europeans who supported stances that expand personal freedoms, such as same-sex marriage, abortion and democratic participation (all positions typically found on the American left) were more likely to choose alternative medicine over conventional.

So, the political divide on health doesn’t go left to right but top-down or bottom-up. When it comes to health, the freedom-loving hippies and the anti-Big Pharma anti-maskers now find themselves on the same side. It is not because they agree on all issues, just fundamental issues about bodily autonomy (of course, they argue about which bodies take precedent), personal choice, anti-corruption, skepticism about the motivation of large corporations, medical freedom, and individual health empowerment and participation. The motto: you can (and should) take charge of your health! What an interesting twist in the culture war plot. Maybe the pursuit of health is the very thing that can heal the political divide.

More and more people find themselves in this camp of granola and whey protein. There has been an increase in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the past year. About 38% of Americans and 26% of Europeans use alternative medicine (Nahin et al., 2024; Valtonen et al., 2023). So what drives us away from the mainstream to seek alternative ways to find solutions to our symptoms and strategies to improve our health? Chronic disease, such as metabolic diseases like insulin resistance and mental health concerns, is increasing, despite increased awareness, newer and better drugs, and more healthcare spending. “Medical gaslighting” has become common parlance as sufferers seek help from their doctor for symptoms of peri-menopause, fatigue, and mental health challenges, and are offered band-aid solutions or dismissed entirely.

We are refused lab tests and told it’s all in our heads; we’re just getting older, and nothing can be done. So many of us are left without answers. This is partly because conventional medicine still follows a reductionistic approach that narrows the patient experience to a set of symptoms treated by one targeted solution (often a drug). In contrast, health, particularly managing complex chronic diseases, requires a holistic, or biopsychosocial framework that examines the interconnected facets of individual and social well-being. Our system is not set up for this, but it is something that naturopathic medicine wholeheartedly embraces. And so more and more patients are finding us.

We, the people, have also become skeptical about food. Nutrition advice from the 1970s, which included recommendations to skip butter and pour on more “heart-healthy oils” like seed oils, and consume a diet based in starch, resulted in skyrocketing rates of diabetes and obesity, with 88% of North Americans considered to be metabolically unhealthy (Araujo et. al., 2019). Metabolic health (or lack thereof) directly results from diet and lifestyle factors. We consumed the processed oils they recommended, our waistlines got bigger, and our pain and inflammation got worse. Maybe it’s the food. But then, Harvard publishes a study reiterating the old expert advice that seed oils are better for us than butter (Zhang et al., 2025). And so, it’s no wonder that skepticism grows around these institutions. We don’t know what to believe. So we hide inside our political silos.

Let’s examine the two controversial nutrition trends of the day: increasing dietary protein and avoiding industrially processed seed oils.

Protein

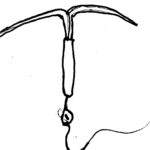

Protein is not just for MAGA bros and hyper-masculine muscle-builders. Eating protein is not embracing toxic masculinity. Protein is a macronutrient obtained from the diet and is essential for survival. Protein comprises our muscle mass, lean mass, bones, joints, hair, skin and cellular proteins and enzymes. Amino acids, the building blocks of protein, make our neurotransmitters, the chemicals that control our mood, appetite, and motivation. Protein stimulates metabolism and controls mood, blood sugar, satiety, and the stress response. It promotes lean mass, which is essential for health and longevity.

We’ve long been aware that the dietary recommendations for protein set in the 1980s are barely adequate to prevent muscle wasting. Current research suggests doubling the recommended daily allowance of protein from 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight to 1.6, putting the recommendation closer to the 0.8 to 1 gram per pound of ideal body weight that the protein “bros” like Peter Attia, Gabrielle Lyon, and Max Lugavare (and I) recommend (Bauer et al., 2013).

When my patients consume more protein, they experience less anxiety, better mood, fewer cravings, and better energy. They don’t eat much processed food that is doctored to include more protein. Instead, they eat like our ancestors have for millennia. They eat more eggs, chicken, beef, fish, tofu, edamame, beans and legumes, and nuts and seeds at their meals.

Seed Oils

When JAMA Internal Medicine, through Harvard, released a study showing that seed oils are better than butter, it seemed like social media erupted (Zhang et al., 2025). Even my brother, who couldn’t give a toss about nutrition, asked me about it. The study examined 210,000 US adults over 30 years and found that butter increased mortality by 15%, while consuming canola, olive and soybean oils decreased all-cause mortality by 16% (Zhang et al., 2025). So, there you go, slather on that soybean oil and you’ll live forever!

The problem with epidemiological studies like this is that they are rife with issues that obfuscate the truth. The first problem is with information gathering. Individuals were asked to report their intake of butter and seed oils using Food Frequency Questionnaires. In other words, they were asked, “How many times in the last week did you consume butter?” I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t know where to start with answering this, and I think about food for a living. After conducting hundreds of nutrition interviews with patients, I can confidently claim that few people know what’s in their food. How did participants know how much butter they were consuming? Foods traditionally made with butter, like pie and other store-bought baked goods, now contain hydrogenated vegetable oils instead. Seed oils are in everything: packaged, fried, and prepared foods. They are cheap and, therefore, the primary cooking oils used in restaurants. It is impossible to completely remove them from an individual’s food supply unless they make a supreme effort to avoid them (basically, if they are one of those conspiracy nuts referred to in the Rolling Stone article).

Also, frustratingly, the seed oils in the study, canola and soybean oil, were grouped with olive oil, one of the healthiest oils. Olive oil differs from seed oils because it is lower in inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids and not industrially processed. It contains polyphenols and monounsaturated fats, which are amazing for heart health and longevity. Olive oil is not an industrial seed oil. This is like putting an A+ student on a group project with D students. It’s entirely possible that olive oil carried the team on this one.

Epidemiological studies contain residual confounders and significant forms of bias, such as Healthy and Unhealthy User Bias. Unhealthy User Bias goes something like this: when you’ve been told that butter is harmful, and continue to consume it, you likely do other things that negatively impact your health. Maybe you drink a bit too much or ride your motorcycle a little too fast. Perhaps you eat more sugar. Maybe you smoke or don’t exercise. The Healthy User Bias works the other way. If you’ve been told that canola oil is heart-healthy, and you care about health, that’s the oil you buy to pour on your broccoli salad before heading to yoga. Factors such as these can drastically impact the study results.

Finally, correlation does not equal causation. The numbers 15% and 16% seem like a lot, but they are modest associations, more susceptible to bias. Correlation can more strongly suggest causation when the relative risk, or strength of the association, is high, such as with smoking and lung cancer. Smoking increases your risk of lung cancer by 2000 to 3000%. The more you smoke, the stronger this association. In light of those numbers, 15% looks relatively weak, right? So, in other words, these study results amount to a big old nothing-burger.

And yet, this study was everywhere. All the news outlets reported on it. It’s telling that the American Heart Association still promotes industrial seed oils while wellness communities, on the left and right, have raised valid concerns about their processing and inflammatory potential. Initially produced for machine lubricants, industrial oils are created from cash crops, like soy, canola and corn, that are often heavily sprayed with pesticides. The grains are then solvent extracted, bleached, and deodorized using a variety of chemicals. They are stripped of nutrients and usually oxidized when they sit on grocery store shelves. They contain a high ratio of omega-6 fatty acids that push pro-inflammatory pathways in the body. When seed oils were brought to market, we saw a marked increase in chronic cardiometabolic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. Of course, this is just a correlation, but it can be plausibly explained by the effect these fats may have on our mitochondria. In contrast, humans have consumed butter for hundreds of years. Butter contains fat-soluble vitamins and butyrate, which is good for the gut.

So, it may be that those who eat more butter fare worse than those who eat “heart-healthy” plant oils, but with much respect to Harvard, I think I’ll pass on the soybean oil.

Similarly, rising protein intake recommendations aren’t just a MAGA phenomenon (to paraphrase Vanity Fair); they reflect a growing body of research on aging, muscle maintenance, and metabolic health. The problem isn’t that people are questioning public health messaging—it’s that public health often fails to earn the public’s trust. Wellness seekers are not irrational or political. Most of these individuals are trying to solve real problems currently unmet by conventional medicine and our public health authorities. Many are cutting edge, integrating scientific research and biological plausibility with self-experimentation. What seems bonkers today may be common knowledge tomorrow, and we’d still be decades behind. Research takes 17 years to reach clinical practice and public health guidelines (Morris et al., 2011). The politicization of wellness says more about the failure of conventional medicine and public health than the people seeking alternatives.

I understand, however, that narratives around personal responsibility can have a right-leaning bent. It’s the whole “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality that ignores systemic barriers. Health empowerment can feel out of reach to people struggling with poverty, food deserts, trauma, and other forms of oppression or hardship. However, I find that many leftist narratives around mental health, aimed at promoting acceptance and compassion, can ignore the reality that mindset, motivation, and behavioural changes matter. You’re not a terrible person or a failure for staying in bed all day, but you will probably feel better if you find the self-compassion and courage to get up and go outside. As a naturopathic doctor and psychotherapist, I don’t shame my patients for their habits. We get curious: what’s blocking you? What do you need? Genuine care involves meeting people where they are and believing they can grow and change. Carl Rogers’ sentiment is, “When I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.” Health is emotional, mental and social, not just physical. Balanced well-being involves days on the couch, eating entire bags of potato chips, and other days spent preparing nourishing meals. Sometimes we need a compassionate nudge to push us in the right direction. Other times, we must be gentle with ourselves, slow down, and rest.

Health is political—not in the sense of group allegiances, but because policies, access, equity, and social context shape it. We need to be wary of flattening health practices into cultural signalling. Personal decisions are not identity markers, signifying what team we’re on. If we care about individual and public health, we must move beyond the binaries, resist shame and talk to one another. What is the best way to help people get well? Is there a framework that values autonomy, freedom, social justice, and collective and personal responsibility? Rather than shaming those who ask questions and seek answers outside the system, how do we create institutions that earn people’s trust?

Political polarization is bad for our health. Instead, let’s shift the conversation toward ways to create more health empowerment. Ultimately, health doesn’t belong to the left or the right. It belongs to humanity.

References:

Araújo, J., Cai, J., & Stevens, J. (2019). Prevalence of optimal metabolic health in american adults: National health and nutrition examination survey 2009–2016. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 17(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2018.0105

Bauer, J., Biolo, G., Cederholm, T., Cesari, M., Cruz‐Jentoft, A. J., Morley, J. E., Phillips, S. M., Sieber, C., Stehle, P., Teta, D., Visvanathan, R., Volpi, E., & Boirie, Y. (2013). Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: A position paper from the prot-age study group. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021

Dickson, E., & Dickson, E. (2023, August 22). Why is the right so obsessed with seed oils? Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/is-seed-oil-bad-for-you-wellness-influencers-right-wing-debunked-1234809499/

Jefferson, T., Dooley, L., Ferroni, E., Al-Ansary, L. A., van Driel, M. L., Bawazeer, G. A., Jones, M. A., Hoffmann, T. C., Clark, J., Beller, E. M., Glasziou, P. P., & Conly, J. M. (2023). Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd006207.pub6

Joffe, A. R. (2021). Covid-19: Rethinking the lockdown groupthink. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.625778

Morris, Z., Wooding, S., & Grant, J. (2011). The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180

Nahin, R. L., Rhee, A., & Stussman, B. (2024). Use of complementary health approaches overall and for pain management by us adults. JAMA, 331(7). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.26775

Polack, F. P., Thomas, S. J., Kitchin, N., Absalon, J., Gurtman, A., Lockhart, S., Perez, J. L., Pérez Marc, G., Moreira, E. D., Zerbini, C., Bailey, R., Swanson, K. A., Roychoudhury, S., Koury, K., Li, P., Kalina, W. V., Cooper, D., Frenck, R. W., Hammitt, L. L.,…Gruber, W. C. (2020). Safety and efficacy of the bnt162b2 mrna covid-19 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(27), 2603–2615. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2034577

Shah, K., Varna, V. P., Sharma, U., & Mavalankar, D. (2022). Does vitamin d supplementation reduce covid-19 severity?: A systematic review. QJM, 115(10). https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcac040

Stefan, N., Birkenfeld, A. L., & Schulze, M. B. (2021). Global pandemics interconnected — obesity, impaired metabolic health and covid-19. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 17(3), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-020-00462-1

Valtonen, J., Ilmarinen, V.-J., & Lonnqvist, J.-E. (2023, August 1). Political orientation predicts the use of conventional and complementary/alternative medicine: A survey study of 19 european countries. Social Science & Medicine, 331. Retrieved May 6, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116089

Weir, K. (2025, May 1). Why are americans so obsessed with protein? blame maga. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/story/protein-maga-craze?srsltid=AfmBOopAY5bfEQI7DfqvBmae8ViGXpZdlvf8G_8AifcOdMspbWd8uNW-

Zhang, Y., Chadaideh, K. S., Li, Y., Li, Y., Gu, X., Liu, Y., Guasch-Ferré, M., Rimm, E. B., Hu, F. B., Willett, W. C., Stampfer, M. J., & Wang, D. D. (2025). Butter and plant-based oils intake and mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine, 185(5), 549. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.0205