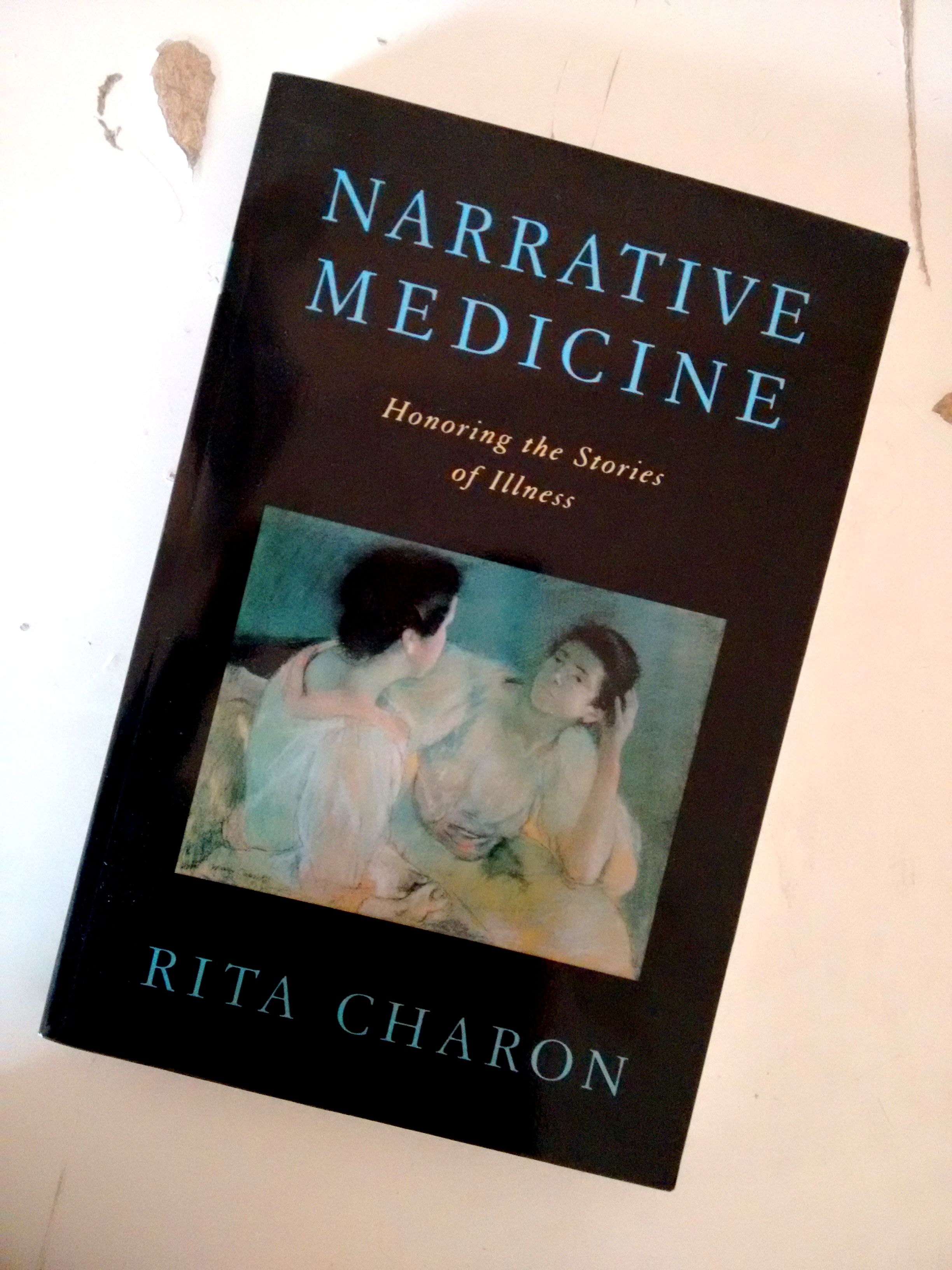

A classmate recently lent me a book that introduced me to the intriguing field of “narrative medicine.” The book is called Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness, written by Rita Charon, MD, an internist practicing in New York City. Narrative medicine combines the practice of medicine with simultaneously learning to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness.

A classmate recently lent me a book that introduced me to the intriguing field of “narrative medicine.” The book is called Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness, written by Rita Charon, MD, an internist practicing in New York City. Narrative medicine combines the practice of medicine with simultaneously learning to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness.

According to the book, the practice of narrative medicine builds empathy and compassion for patients by giving meaning to their experience through stories. It allows doctors to bear witness to the patients and their suffering and to enable those who are suffering to be heard, thus making their care more effective and, by virtue of the doctor’s presence and ability to testify to the patient’s pain, the pain is lessened somewhat.

The Need for Narrative in Modern and Natural Medicine

Rita writes, “the medical impulse toward replicability and universality has muted doctors’ realization of the singularity and creativity of their acts of observation and description.” In medical school we come to learn that, when asked to choose between a) b) c) d) or e), all of the above, there can only be one right answer. Through these educative measures, we are led to believe that there is no room for creativity or individuality in medicine. Narrative medicine, however, begins to challenge that belief. According to Dr. Charon, there is a struggle in medicine to balance the need to properly observe the phenomenon of the individual patient and his or her particular clinical presentation before us, with the need to fit people into diagnostic categories. Oftentimes, the scale tips to the latter, simply by nature of patient volume or ease of the encounter. When we fit people into categories we can ease the anxiety that comes with uncertainty. We are soothed by the security of being right, the same way we are soothed by correctly choosing c) on a multiple choice exam. Patients, however, have come to resent this aspect of modern medicine. Rita writes, “patients complain that doctors or hospitals treat them like numbers or like items on an assembly line. They lament that their singularity is not valued and that they have been reduced to that level at which they repeat other human bodies.” In Rita Charon’s eyes, however, we are beginning to see a new emergence of both doctors and patients taking back the right to patient individuality in medical care. We naturopathic doctors hear this often, when asking why a patient decided to come to see us in lieu of a medical doctor, and hearing that they were driven by the need to be treated “like a person”, not just a disease.

Our bodies and our health are integral parts of the narratives of our lives. And so a personal medical history that, in the case of a medical school exam, takes about 8-10 minutes to complete, actually carries in it the patient’s life story. Everything that the body have been through the self has also been through and whatever has happened to the body remains ingrained in the self and forms a part of the patient’s narrative. Kathryn Montgomery, a colleague of Rita Charon’s once said, “you can accomplish an entire medical interview by simply asking a patient, “tell me about your scars.'”

Dr. Rita Charon writes, “without doubt, the teller and the listener in the clinical setting work together to discover or create the plot of their concerns. The better equipped clinicians are to listen for or read for a plot, the more accurately will they entertain likely diagnoses and be alert for unlikely but possible ones. To have developed methods of searching for plot or even imagining what the plot might be equips clinicians to wait, patiently, for a diagnosis to declare itself, confident that eventually the fog will rise and the contours of meaning will become clear.” Narrative, we learn, is essential for understanding illness.

Receiving a Patient History

Sir Richard Bayliss, another colleague of Charon’s, writes, “not only must the physician hear what is said but with a trained ear he or she must listen to the exact words that the patient uses and the sequence in which they are uttered. Histories must be received, not taken.”

Rita Charon’s current method of “receiving” a patient history is described eloquently in her book. It differs so much from the style we are taught in medical school, that I feel it is worth sharing. She writes that, when she first meets a patient, she begins by saying, “tell me what you think I should know about your situation.” She then makes the commitment to listen, without speaking or writing anything down. In medical school we are taught to organize a chart by history of presenting illness, past medical history, family history, etc. However, Charon realized that, by allowing the patient to direct his or her own clinical interview, the information all comes out eventually. She believes it is crucial to allow the patients to narrate their own history, allowing the information to take its own order, to formulate itself into not just a coherent plot but also a literary form, so that the entire story becomes apparent, and free from her own bias and internal or external editing. While the patient tells his or her story, Dr. Charon listens as intently as she can, registering diction, form, images and the pace of speech emitted from the patient’s mouth. She tries not to interrupt or confer signs of encouragement, pleasure or disapproval. She refrains from asking questions. And, she takes the time to absorb the metaphors, idioms, accompanying gestures, plot and characters involved in the patient’s narrative.

Once her patient has finished with his or her telling, Dr. Charon proceeds to the physical exam portion of the clinical visit. She tries to capture what has been said by writing the story down in her chart while the patient changes into his or her gown and readies for the physical examination.

Dr. Charon writes that it has taken her a while to perfect this form of receiving a patient history. As unorthodox as it may seem, she writes that she has come to thoroughly enjoy the individuality and humanity of the stories that come from each person, each one so different from any other and each belonging to a singular person and body. It has helped her understand her patients, maintain empathy for them and provide them with what she believes is more effective care.

The Parallel Chart

Rita Charon believes that, not only is the use of narrative helpful for the doctor-patient relationship, it can be used to help physicians and other healthcare practitioners digest their experience as well. In one of her years as a clinical supervisor, she developed a practice called the Parallel Chart. As medical students and doctors, we are required to write our patient’s stories in the form of medical charts, following a specific format, creating what can be viewed as an entire literary genre used solely among medical professionals. Medical students and doctors alike are expected to learn to write and maintain a coherent medical chart, according to the standards of this genre.

However, as a clinical supervisor, Rita Charon also has her young precepts write a Parallel Chart, one that will not be filed for reference but that is just for the benefit of the practitioner, written in plain language, about one of his or her patients. She tells her students, “every day you write in the hospital chart about each of your patients. You know exactly what to write there and the form in which to write it. You write about your patient’s current complaints, the results of the physical exam, laboratory findings, opinions of consultants, and the plan. If your patient dying of prostate cancer reminds you of your grandfather, who died of that disease last summer, and each time you go into the patient’s room, you weep for your grandfather, you cannot write that in the hospital chart. We will not let you. And yet it has to be written somewhere. You write it in the Parallel Chart.”

After giving her students these instructions, Rita Charon meets with them in a group once a month and gives everyone the chance to read a Parallel Chart entry of their choice out loud. After the reading, she proceeds to comment on the genre, temporality, metaphors, structure and style of the text that has been written, using her literary background as a guide. The other students then have a chance to respond to the text, creating a dialogue surrounding their clinical experiences.

She reflects that her students in the past have written about their deep attachment to patients, their feelings of helplessness in the clinical encounter in their role as mere medical students, the rage, shame and humiliation they experience in the face of disease as well as their awe at patients’ courage. Dr. Rita Charon claims that the students who undertake the task of keeping a Parallel Chart have found that they are more in touch with their own emotions during the clinical encounter, feel deeper empathy for their patients and fellow colleagues and are able to understand their patients more fully. Research is even being conducted at Columbia University to evaluate the effectiveness of Parallel Charting, finding that physicians who engage in this practice are more proficient and effective at conducting medical interviews, performing medical procedures and developing doctor-patient relationships with patients.

In many ways, naturopathic medicine already acknowledges the importance of patient story-telling when it comes to healing from disease. We treat people as individuals and look for the root cause of illness, taking into account the story behind each of our patient’s “scars”. However, as our school curriculum becomes more medicalized and primary care-focused, I believe that our need to conduct efficient medical interviews and develop effective treatment plans is in danger of displacing our inherent philosophies. Taking the time to read Rita Charon’s book opened my eyes to the importance of patient individuality and respect for patient narrative. To understand illness, it is essential to integrate narrative into the framework of the clinical encounter by giving patients the space to tell, while also giving ourselves, the practitioners, the space for our own telling with the intention of becoming better, more empathetic doctors.

My primary physician’s office interviews you when you make an appointment, so they know how long you will need with the doctor – less than 30 minutes, 30 to 45 minutes, an hour to an hour and half. My primary physcian is holistic as well as westernized and love that! Plus I have become my own patient advocate and have handed over to my primary my family’s health history and continue to add to that history. It is not easy just laying it out there, but I am lucky in that I have a primary that I trust and we can come together if necessary on a treatment plan. Great Post – Happy Monday – thanks so much for sharing:)

Sounds like you lucked out on an amazing family doctor: 1.5 hour appointments, and an integrated approach! It’s great that you’re taking charge of your health, ensuring you have a complete chart. Sometimes patients need to take responsibility for their own health – doing their own research, keeping track of their files and deciding on which specialists/alternative practitioners to consult. Gone are the days when they sat back passively and let the doctors make the decisions. Happy Monday!

Ordering this book right now! Sounds exactly what I’ve been looking for! Thanks for sharing… And to Fernando (probably, he always has the best books!)!!!

You’re right, it was totally Fernando! Yes, read it! In the meantime here is a JAMA article by her and a TedTalk: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=194300

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=24kHX2HtU3o

Great post Talia! I watched her Ted Talk, and a lot of really great stuff came up as well. Thanks for bringing up these topics! Seems like we’ve got some positive traction on how the curriculum is going to change, and now it’s just a matter of how it gets rolled out. We’ll make sure to have a lot of conversations around these topics during fourth year though!

I certainly hope we do! I would love to learn to incorporate what she’s experienced into naturopathic practice.

I’m not sure if I would feel any better by a story but if it works for only one person, it’s worth it. Many doctors today seem to just want to get in and out fast and it seems like you can barely get your problem out on the table before they are looking to rush out to the next patient. I guess that’s a result of our healthcare system, I don’t know but I find it hard to connect with most doctors which is what I think would make the most difference.

Reblogged this on Donna Lasnowski.

I’m a new intern at the RSNC, and this is exactly what I needed to read after my first month in practice. Thank you!!

Yes, Laura! This post will help you like crazy! May I also suggest the Motivational Interviewing course at OISE? It changed my practice and interviewing skills. Incredible.