by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jul 9, 2016 | Acupuncture, Art, Art Therapy, Balance, Community, Depression, Emotions, Empathy, Health, Meditation, Mental Health, Mind Body Medicine, Mindfulness, Psychology, Self-care

It seems like the world is falling apart. These days more than ever.

It seems like the world is falling apart. These days more than ever.

Race wars, weapons, war, wealth concentrated into the hands of a few, and violence, Facebook is filled with videos that fill our heads and hearts with a complicated mixture of sadness, anger, anguish, confusion, frustration, enrage, injustice and a deep-felt sense of powerlessness. We struggle through these events to go on living—to go about our lives in a dignified fashion, to pay our rent, to engage our relationships, to find happiness and satisfaction in our lots in this world. It seems like the world is ending, and yet we still have our daily responsibilities. Our cynicism is engaged; our idealism is crumbling. Many of us feel hope leaving our bodies. Many of us feel frustration morphing into despair.

Stress is estimated to be the number one cause of disease. As a naturopathic doctor, my role often involves cleaning up the debris from chronic, long-term stress responses gone haywire. Oftentimes my patients don’t even perceive the stress they’re under. “I’m type A! I thrive under stress and pressure”, some will tell me. Other times the people I work with are so far in a state of overwhelm it’s all they can do to keep moving forward with their daily routines.

The World Health Organization estimates that 75-90% of doctor’s visits are attributed to by stress. I would estimate that 100% of the people I work with have on-going stress in their lives.

We doctors know that some people, the “Type B’s” in society, are more susceptible to stress. We know these people, we may even be one of them ourselves: the sensitive individuals, the intuitives, the feelers, the artists, empaths, activists and light-workers. We are individuals who are often drawn to artistic and healing professions, who care deeply about relationships, people, feelings and soft-ness in this world. We often find ourselves pushed up against hard edges, struggling to pay bills and cope with cruelty and injustice. We face daily struggles and the pain of living a disconnected, yet intricately interdependent life in modern-day society. Some natural doctors have terms us “parasympathetic dominants”—people whose nervous systems tend to get stuck in the parasympathetic (as opposed to stress-fuelled sympathetic) arm of the autonomic nervous system (the “automatic” nervous system).

We often feel overcome with a sense of overwhelm when faced with packed schedules, high stakes jobs that affect others, achievement-oriented striving and the prioritization of money and numbers over people. In this world of deadlines, assertion, aggression, fear, war and material wealth, we can often feel like we don’t fit in. We can suffer from burnout.

Burnout, “adrenal fatigue” or “parasympathetic dominance” happens when our stress response becomes depleted. It is characterized by naturopathic doctors as fatigue, excessive needs for sleep and quiet, lack of motivation, disrupted sleep schedules, difficulty losing weight, sluggish digestion, bloating and IBS, headaches and brain fog, poor memory, hormonal imbalance resulting in heavy or irregular periods, PMS, infertility and acne. Mental illness can begin to surface or worsen in this state, resulting in depression, anxiety, or even bipolar disorder and psychosis. The narrative of the mad, artistic genius, burdened by the weight and troubles of the world, surfaces to mind—the creative genius who is too sensitive for this world. We run the risk of becoming irritable, and losing some of our natural compassion as we drift off into exhausted survival mode.

Many of the people I work with are these sensitive individuals, myself included, and I’m proud to help this population. Through healing the sensitive feelers, we heal the world. The world needs a little more softness and more compassion. It needs people who can pick up on emotional nuances and care deeply about others. It needs people who listen, who feel, who create and share their versions of the human experience to teach others. Through the artists, we experience the depths of our own humanity. Through the artists, we see our pain and, through seeing our pain, we can begin to heal it. It is important that we can find fulfilling work and lives that nurture us, so that we may have the energy to extend our gifts to the world.

Healing parasympathetic dominance in my practice often manifests first as establishing a therapeutic relationship. We crave openness, time and space to explore emotional nuances and engage our natural sense of curiosity. We crave being deeply heard and felt. As a doctor, I do my best to listen, not just to the words, but the space between them, and the symptoms of the body. We look for root causes to issues so that we can establish lifestyle patterns that nurture us.

Creating a clean, nutritious diet: With lean protein, usually meats that stimulate metabolism and manage stress, healthy fats, anti-inflammatory nutrients and lots of fruits and vegetables, especially berries and leafy greens, we can begin to re-feed ourselves and heal inflammation.

Gentle, nurturing movement: I often suggest exercise that blends into the lifestyles of my patients, that works with them. Slow, meditative walking for an hour a day is a wonderful, scientifically proven method of bringing down stress hormone levels. It also creates space in the day for contemplation and integration.

Restful sleep: Through sleep hygiene and some strategically dosed supplements, improving sleep allows the body to repair itself and rest. Those suffering from burnout may need more sleep. Dealing with the guilt that can arise through sleeping in and saying no to non-essential activities to prioritize sleep is often a psychological hurdle in those who feel best when they are nurturing and giving to others, and not themselves.

Self-care: Journalling, meditation and engaging in creative pursuits are helpful armour in allowing one to integrate, express and stay open, energized and creative.

Nurturing mental health and emotions: Speaking to family and friends or a trained therapist or naturopathic doctor can allow us to dive more deeply into our own psyches. When we explore the corners of our mind we are able to heal mental-emotional obstacles to health and learn more about ourselves and others and alter the way we engage in the world. Opening ourselves up to deep-seated anger, fear and sadness is essential to clearing this repressed emotions and improving our experience in the world. My favourite forms of talk therapy are Narrative Therapy and Coherence Therapy. Both involve openly engaging the emotional and mental experience of the other to alter core beliefs and narratives and explore possibilities for living a preferred life experience.

Through the times we are facing, I urge us all to band together, embrace the healers and artists among us and engage in deep, nurturing self-care. Journal, spend time with friends and create. Take time from your activist pursuits and political readings to reflect, to meditate, to get some healing acupuncture and to cry or express anger. Feel the emotions that arise during this time. Take the time to listen to the narratives that emerge. Eat a diet filled with protein, try to keep to a sleep schedule, if possible. Nurture yourself and the complicated emotions that are arising within you and others.

We need you to help us through this time. It is people like you who can heal others, but only if you strive to heal yourself as well.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Feb 23, 2016 | Art, Art Therapy, Balance, Culture, Digestion, Docere, Education, Emotions, Finding yourself, Happiness, Healing Stories, Health, Letting Go, Lifestyle, Listening, Love, Medicine, Meditation, Mental Health, Mind Body Medicine, Mindfulness, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Patience, Philosophy, Psychology, Reflections, Self-care, Self-reflection

Today, I’m 30, working on my career as a self-employed health professional and a small business owner and living on my own. I’ve moved through a lot of states, emotions and life experiences this year, which has been appropriate for closing the chapter on my 20’s and moving into a new decade of life. I’ve experienced huge changes in the past year and significant personal growth thanks to the work I’ve been blessed to do and the people who have impacted me throughout the last 30 years. Here are 30 things this past year has taught me.

Today, I’m 30, working on my career as a self-employed health professional and a small business owner and living on my own. I’ve moved through a lot of states, emotions and life experiences this year, which has been appropriate for closing the chapter on my 20’s and moving into a new decade of life. I’ve experienced huge changes in the past year and significant personal growth thanks to the work I’ve been blessed to do and the people who have impacted me throughout the last 30 years. Here are 30 things this past year has taught me.

- Take care of your gut and it will take care of you. It will also eliminate the need for painkillers, antidepressants, skincare products, creams, many cosmetic surgeries, shampoo and a myriad of supplements and products.

- Trying too hard might not be the recipe for success. In Taoism, the art of wu wei, or separating action from effort might be key in moving forward with your goals and enjoying life; You’re not falling behind in life. Additionally, Facebook, the scale and your wallet are horrible measures to gauge how you’re doing in life. Find other measures.

- If you have a chance to, start your own business. Building a business forces you to build independence, autonomy, self-confidence, healthy boundaries, a stronger ego, humility and character, presence, guts and strength, among other things. It asks you to define yourself, write your own life story, rewrite your own success story and create a thorough and authentic understanding of what “success” means to you. Creating your own career allows you to create your own schedule, philosophy for living and, essentially, your own life.

- There is such as thing as being ready. You can push people to do what you want, but if they’re not ready, it’s best to send them on their way, wherever their “way” may be. Respecting readiness and lack thereof in others has helped me overcome a lot of psychological hurdles and avoid taking rejection personally. It’s helped me accept the fact that we’re all on our own paths and recognize my limitations as a healer and friend.

- Letting go is one of the most important life skills for happiness. So is learning to say no.

- The law of F$%3 Yes or No is a great rule to follow, especially if you’re ambivalent about an impending choice. Not a F— Yes? Then, no. Saying no might make you feel guilty, but when the choice is between feeling guilty and feeling resentment, choose guilt every time. Feeling guilty is the first sign that you’re taking care of yourself.

- Patience is necessary. Be patient for your patients.

- Things may come and things may go, including various stressors and health challenges, but I will probably always need to take B-vitamins, magnesium and fish oil daily.

- Quick fixes work temporarily, but whatever was originally broken tends to break again. This goes for diets, exercise regimes, intense meditation practices, etc. Slow and steady may be less glamorous and dramatic, but it’s the only real way to change and the only way to heal.

- When in doubt, read. The best teachers and some of the best friends are books. Through books we can access the deepest insights humanity has ever seen.

- If the benefits don’t outweigh the sacrifice, you’ll never give up dairy, coffee, wine, sugar and bread for the long term. That’s probably perfectly ok. Let it go.

- Patients trust you and then they heal themselves. You learn to trust yourself, and then your patients heal. Developing self-trust is the best continuing education endeavour you can do as a doctor.

- Self-care is not selfish. In fact, it is the single most powerful tool you have for transforming the world.

- Why would anyone want to anything other than a healer or an artist?

- Getting rid of excess things can be far more healing than retail therapy. Tidying up can in fact be magical and life-changing.

- It is probably impossible to be truly healthy without some form of mindfulness or meditation in this day and age.

- As Virginia Woolf once wrote, every woman needs a Room of Own’s Own. Spending time alone, with yourself, in nature is when true happiness can manifest. Living alone is a wonderful skill most women should have—we tend to outlive the men in our lives, for one thing. And then we’re left with ourselves in the end anyways.

- The inner self is like a garden. We can plant the seeds and nurture the soil, but we can’t force the garden to grow any faster. Nurture your garden of self-love, knowledge, intuition, business success, and have faith that you’ll have a beautiful, full garden come spring.

- Be cheap when it comes to spending money on everything, except when it comes to food, travel and education. Splurge on those things, if you can.

- Your body is amazing. Every day it spends thousands of units of energy on keeping you alive, active and healthy. Treat it well and, please, only say the nicest things to it. It can hear you.

- If you’re in a job or life where you’re happy “making time go by quickly”, maybe you should think of making a change. There is only one February 23rd, 2016. Be grateful for time creeping by slowly. When you can, savour the seconds.

- Do no harm is a complicated doctrine to truly follow. It helps to start with yourself.

- Drink water. Tired? Sore? Poor digestion? Weight gain? Hungry? Feeling empty? Generally feeling off? Start with drinking water.

- Do what you love and you’ll never have to work a day in your life. As long as what you love requires no board exams, marketing, emailing, faxing, charting, and paying exorbitant fees. But, since most careers have at least some of those things, it’s still probably still preferable to be doing something you love.

- Not sure what to do? Pause, count to 7, breathe. As a good friend and colleague recently wrote to me, “I was doing some deep breathing yesterday and I felt so good.” Amen to that.

- As it turns out, joining a group of women to paint, eat chocolate and drink wine every Wednesday for two months can be an effective form of “marketing”. Who knew?

- “Everyone you meet is a teacher”, is a great way to look at online dating, friendships and patient experiences. Our relationships are the sharpest mirrors through which we can look at ourselves. Let’s use them and look closely.

- Being in a state of curiosity is one of the most healing states to be in. When we look with curiosity, we are unable to feel judgment, anxiety, or obsess about control. Curiosity is the gateway to empathy and connection.

- Aiming to be liked by everyone prevents us from feeling truly connected to the people around us. The more we show up as our flawed, messy, sometimes obnoxious selves, the fewer people might like us. However, the ones who stick around happen to love the hot, obnoxious mess they see. As your social circle tightens, it will also strengthen.

- If everyone is faking it until they make it, then is everyone who’s “made” it really faking it? These are the things I wonder while I lie awake at night.

Happy Birthday to me and happy February 23rd, 2016 to all of you!

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jul 20, 2015 | Art Therapy, Community, Creativity, Docere, Education, Emotions, Empathy, Finding yourself, Healing Stories, Health, Medicine, Mental Health, Mind Body Medicine, Mindfulness, Narrative Therapy, Philosophy, Politics, Psychology, Relationships, Self-reflection, Treating the Cause, Volunteering

As a child, I was obsessed with stories. I wrote and digested stories from various genres and mediums. I created characters, illustrating them, giving them clothes and names and friends and lives. I threw them into narratives: long stories, short stories, hypothetical stories that never got written. Stories are about selecting certain events and connecting them in time and sequence to create meaning. In naturopathic medicine I found a career in which I could bear witness to people’s stories. In narrative therapy I have found a way to heal people through helping them write their life stories.

As a child, I was obsessed with stories. I wrote and digested stories from various genres and mediums. I created characters, illustrating them, giving them clothes and names and friends and lives. I threw them into narratives: long stories, short stories, hypothetical stories that never got written. Stories are about selecting certain events and connecting them in time and sequence to create meaning. In naturopathic medicine I found a career in which I could bear witness to people’s stories. In narrative therapy I have found a way to heal people through helping them write their life stories.

We humans create stories by editing. We edit out events that seem insignificant to the formation of our identity. We emphasize certain events or thoughts that seem more meaningful. Sometimes our stories have happy endings. Sometimes our stories form tragedies. The stories we create shape how we see ourselves and what we imagine to be our possibilities for the future. They influence the decisions we make and the actions we take.

We use stories to understand other people, to feel empathy for ourselves and for others. Is there empathy outside of stories?

I was seeing R, a patient of mine at the Yonge Street Mission. Like my other patients at the mission health clinic, R was a young male who was street involved. He had come to see me for acupuncture, to help him relax. When I asked him what brought him in to see me on this particular day, his answer surprised me in its clarity and self-reflection. “I have a lot of anger,” He said, keeping his sunglasses on in the visit, something I didn’t bother to challenge.

R spoke of an unstoppable rage that would appear in his interactions with other people. Very often it would result in him taking violent action. A lot of the time that action was against others. This anger, according to him, got him in trouble with the law. He was scared by it—he didn’t really want to hurt others, but this anger felt like something that was escaping his control.

We chatted for a bit and I put in some acupuncture needles to “calm the mind” (because, by implication, his mind was not currently calm). After the treatment, R left a little lighter with a mind that was supposedly a little calmer. The treatment worked. I attributed this to the fact that he’d been able to get some things off his chest and relax in a safe space free of judgment. I congratulated myself while at the same time lamented the sad fact that R was leaving my safe space and re-entering the street, where he’d no doubt go back to floundering in a sea of crime, poverty and social injustice. I sighed and shrugged, feeling powerless—this was a fact beyond my control, there wasn’t anything I could do about it.

The clinic manager, a nurse practitioner, once told me, “Of course they’re angry. These kids have a lot to be angry at.” I understood theoretically that social context mattered, but only in the sense that it posed an obstacle to proper healing. It is hard to treat stress, diabetes, anxiety and depression when the root causes or complicating factors are joblessness, homelessness and various traumatic experiences. A lot of the time I feel like I’m bailing water with a teaspoon to save a sinking ship; my efforts to help are fruitless. This is unfortunate because I believe in empowering my patients. How can I empower others if I myself feel powerless?

I took a Narrative Therapy intensive workshop last week. In this workshop we learn many techniques for empowering people and healing them via the formation of new identities through storytelling. In order to do this, narrative therapy extricates the problem from the person: the person is not the problem, the problem is the problem. Through separating problems from people, we are giving our patients the freedom to respond to or resolve their problems in ways that are empowering.

Naturopathic doctors approach conditions like diabetes from a life-style perspective; change your lifestyle and you can change your health! However, when we fail to separate the patient from the diabetes, we fail to examine the greater societal context that diabetes exists in. For one thing, our culture emphasizes stress, overwork and inactivity. The majority of food options we are given don’t nourish our health. Healthy foods cost more; we need to work more and experience more stress in order to afford them. We are often lied to when it comes to what is healthy and what is not—food marketing “healthwashes” the food choices we make. We do have some agency over our health in preventing conditions like diabetes, it’s true, but our health problems are often created within the context in which we live. Once we externalize diabetes from the person who experiences it, we can begin to distance our identities from the problem and work on it in creative and self-affirming ways.

Michael White, one of the founders of Narrative Therapy says,

If the person is the problem there is very little that can be done outside of taking action that is self-destructive.

Many people who seek healthcare believe that their health problems are a failure of their bodies to be healthy—they are in fact the problem. Naturopathic medicine, which aims to empower people by pointing out they can take action over their health, can further disempower people when we emphasize action and solutions that aim at treating the problems within our patients—we unwittingly perpetuate the idea that our solutions are fixing a “broken” person and, even worse, that we hold the answer to that fix. If we fail to separate our patients from their health conditions, our patients come to believe that their problems are internal to the self—that they or others are in fact, the problem. Failure to follow their doctor’s advice and heal then becomes a failure of the self. This belief only further buries them in the problems they are attempting to resolve. However, when health conditions are externalized, the condition ceases to represent the truth about the patient’s identity and options for healing suddenly show themselves.

While R got benefit from our visit, the benefit was temporary—R was still his problem. He left the visit still feeling like an angry and violent person. If I had succeeded in temporarily relieving R of his problem, it was only because I had acted. At best, R was dependent on me. At worst, I’d done nothing, or, even worse, had perpetuated the idea that there was something wrong with him and that he needed fixing.

These kids have a lot to be angry at,

my supervisor had said.

R was angry. But what was he angry at? Since I hadn’t really asked him, at this time I can only guess. The possibilities for imagining answers, however, are plentiful. R and his family had recently immigrated from Palestine, a land ravaged by war, occupation and racial tension. R was street-involved, living in poverty in an otherwise affluent country like Canada. I wasn’t sure of his specific relationship to poverty, because I hadn’t inquired, but throughout my time at the mission I’d been exposed to other narratives that may have intertwined with R’s personal storyline. These narratives included themes of addiction, abortion, hunger, violence, trauma and abandonment, among other tragic experiences. If his story in any way resembled those of the other youth who I see at the mission, it is fair to say that R had probably experienced a fair amount of injustice in his young life—he certainly had things to be angry at. I wonder if R’s anger wasn’t simply anger, but an act of resistance against injustice against him and others in his life: an act of protest.

“Why are you angry?” I could have asked him. Or, even better, “What are you protesting?”

That simple question might have opened our conversation up to stories of empowerment, personal agency, skills and knowledge. I might have learned of the things he held precious. We might have discussed themes of family, community and cultural narratives that could have developed into beautiful story-lines that were otherwise existing unnoticed.

Because our lives consist of an infinite number of events happening moment to moment, the potential for story creation is endless. However, it is an unfortunate reality that many of us tell the same single story of our lives. Oftentimes the dominant stories we make of our lives represent a problem we have. In my practice I hear many problem stories: stories of anxiety, depression, infertility, diabetes, weight gain, fatigue and so on. However, within these stories there exist clues to undeveloped stories, or subordinate stories, that can alter the way we see ourselves. The subordinate stories of our lives consist of values, skills, knowledge, strength and the things that we hold dear. When we thicken these stories, we can change how we see ourselves and others. We can open ourselves up to greater possibilities, greater personal agency and a preferred future in which we embrace preferred ways of being in the world.

I never asked R why the anger scared him, but asking might have provided clues to subordinate stories about what he held precious. Why did he not want to hurt others? What was important about keeping others safe? What other things was he living for? What things did he hope for in his own life and the lives of others? Enriching those stories might have changed the way he was currently seeing himself—an angry, violent youth with a temper problem—to a loving, caring individual who was protesting societal injustice. We might have talked about the times he’d felt anger but not acted violently (he’d briefly mentioned turning to soccer instead) or what his dreams were for the future. We might have talked about the values he’d been taught—why did he think that violence was wrong? Who taught him that? What would that person say to him right now, or during the times when his anger was threatening to take hold?

Our visit might have been powerful. It might have opened R up to a future of behaving in the way he preferred. It might have been life-changing.

It definitely would have been life-affirming.

Very often in the work we do, we unintentionally affirm people’s problems, rather than their lives.

One of the course participants during my week-long workshop summed up the definition of narrative therapy in one sentence,

Narrative therapy is therapy that is life-affirming.

And there is something very healing in a life affirmed.

More:

The Narrative Therapy Centre: http://www.narrativetherapycentre.com/

The Dulwich Centre: http://dulwichcentre.com.au/

Book: Maps of Narrative Practice by Michael White

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Apr 30, 2014 | Art, Art Therapy, Balance, Creativity, Health, Mental Health, Psychology, Stress, Student

I know about the healing power of art. Sitting in front of a painting and quietly filling in a private world of colour helps to open up the right side of the brain, dissolving the hard edges of worn thought patterns and softening us to possibility. I know that wonderful realizations arise from the quiet space that art can provide. Bright colours draw attention to inner darkness. Self-criticism becomes louder and steps out into the light, allowing us to properly examine it.

Therefore, when I decided to attend an art therapy workshop, I figured myself to be already part of the choir who I thought would be preached to. I knew that art held the magical power to do deep psychological work. I was just curious as to how that would look in a therapeutic setting.

(more…)

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Oct 27, 2013 | Art, Art Therapy, Meditation, Philosophy, Poetry, Writing

Medicine is an art form; each chart is a blank canvas on which we document the interconnection between ourselves and our patient. Through medicine we allow patients to publish their own autobiographies, as we ghost-write it, pen to paper, in our medical charts.

(more…)

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Apr 8, 2013 | Art, Art Therapy, Book Review, Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, Creativity, Empathy, Healing Stories, Listening, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Philosophy, Psychology, Student, Writing

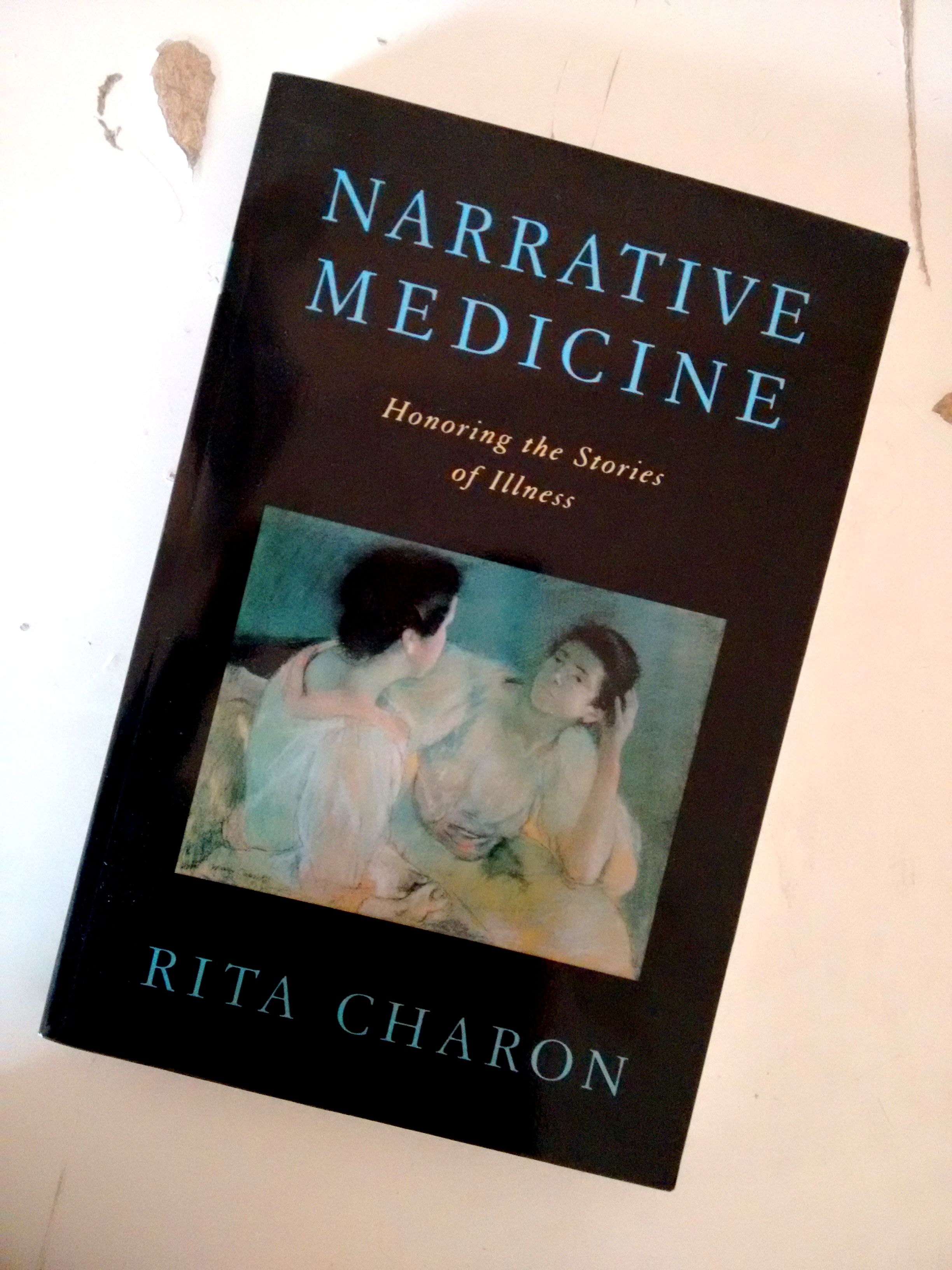

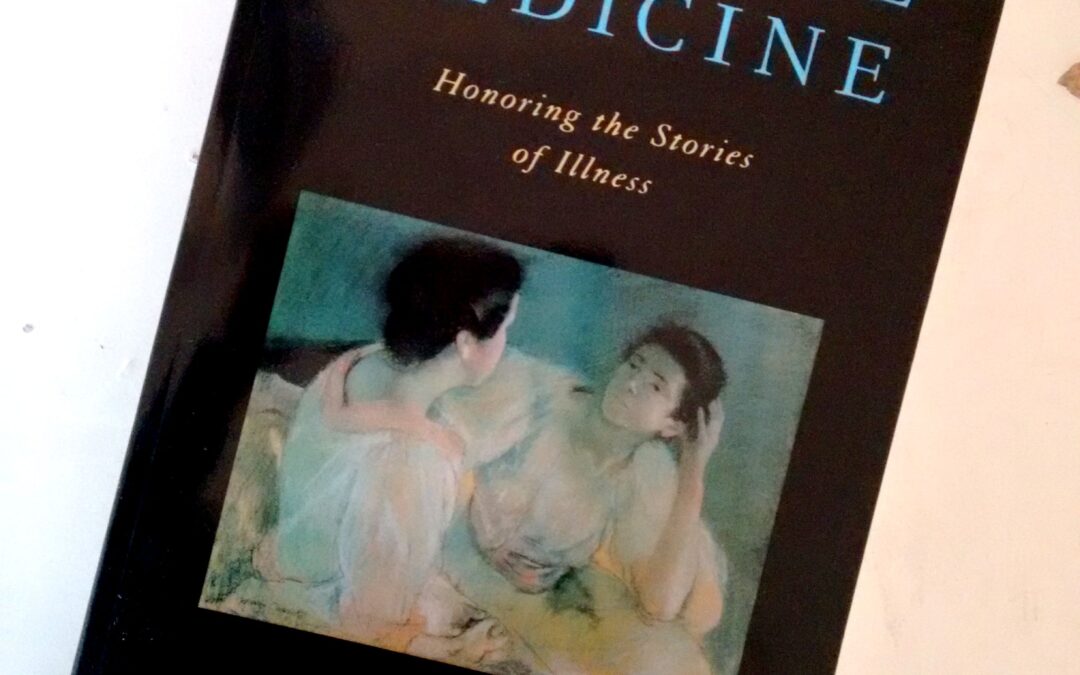

A classmate recently lent me a book that introduced me to the intriguing field of “narrative medicine.” The book is called Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness, written by Rita Charon, MD, an internist practicing in New York City. Narrative medicine combines the practice of medicine with simultaneously learning to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness.

A classmate recently lent me a book that introduced me to the intriguing field of “narrative medicine.” The book is called Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness, written by Rita Charon, MD, an internist practicing in New York City. Narrative medicine combines the practice of medicine with simultaneously learning to recognize, absorb, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness.

According to the book, the practice of narrative medicine builds empathy and compassion for patients by giving meaning to their experience through stories. It allows doctors to bear witness to the patients and their suffering and to enable those who are suffering to be heard, thus making their care more effective and, by virtue of the doctor’s presence and ability to testify to the patient’s pain, the pain is lessened somewhat.

The Need for Narrative in Modern and Natural Medicine

Rita writes, “the medical impulse toward replicability and universality has muted doctors’ realization of the singularity and creativity of their acts of observation and description.” In medical school we come to learn that, when asked to choose between a) b) c) d) or e), all of the above, there can only be one right answer. Through these educative measures, we are led to believe that there is no room for creativity or individuality in medicine. Narrative medicine, however, begins to challenge that belief. According to Dr. Charon, there is a struggle in medicine to balance the need to properly observe the phenomenon of the individual patient and his or her particular clinical presentation before us, with the need to fit people into diagnostic categories. Oftentimes, the scale tips to the latter, simply by nature of patient volume or ease of the encounter. When we fit people into categories we can ease the anxiety that comes with uncertainty. We are soothed by the security of being right, the same way we are soothed by correctly choosing c) on a multiple choice exam. Patients, however, have come to resent this aspect of modern medicine. Rita writes, “patients complain that doctors or hospitals treat them like numbers or like items on an assembly line. They lament that their singularity is not valued and that they have been reduced to that level at which they repeat other human bodies.” In Rita Charon’s eyes, however, we are beginning to see a new emergence of both doctors and patients taking back the right to patient individuality in medical care. We naturopathic doctors hear this often, when asking why a patient decided to come to see us in lieu of a medical doctor, and hearing that they were driven by the need to be treated “like a person”, not just a disease.

Our bodies and our health are integral parts of the narratives of our lives. And so a personal medical history that, in the case of a medical school exam, takes about 8-10 minutes to complete, actually carries in it the patient’s life story. Everything that the body have been through the self has also been through and whatever has happened to the body remains ingrained in the self and forms a part of the patient’s narrative. Kathryn Montgomery, a colleague of Rita Charon’s once said, “you can accomplish an entire medical interview by simply asking a patient, “tell me about your scars.'”

Dr. Rita Charon writes, “without doubt, the teller and the listener in the clinical setting work together to discover or create the plot of their concerns. The better equipped clinicians are to listen for or read for a plot, the more accurately will they entertain likely diagnoses and be alert for unlikely but possible ones. To have developed methods of searching for plot or even imagining what the plot might be equips clinicians to wait, patiently, for a diagnosis to declare itself, confident that eventually the fog will rise and the contours of meaning will become clear.” Narrative, we learn, is essential for understanding illness.

Receiving a Patient History

Sir Richard Bayliss, another colleague of Charon’s, writes, “not only must the physician hear what is said but with a trained ear he or she must listen to the exact words that the patient uses and the sequence in which they are uttered. Histories must be received, not taken.”

Rita Charon’s current method of “receiving” a patient history is described eloquently in her book. It differs so much from the style we are taught in medical school, that I feel it is worth sharing. She writes that, when she first meets a patient, she begins by saying, “tell me what you think I should know about your situation.” She then makes the commitment to listen, without speaking or writing anything down. In medical school we are taught to organize a chart by history of presenting illness, past medical history, family history, etc. However, Charon realized that, by allowing the patient to direct his or her own clinical interview, the information all comes out eventually. She believes it is crucial to allow the patients to narrate their own history, allowing the information to take its own order, to formulate itself into not just a coherent plot but also a literary form, so that the entire story becomes apparent, and free from her own bias and internal or external editing. While the patient tells his or her story, Dr. Charon listens as intently as she can, registering diction, form, images and the pace of speech emitted from the patient’s mouth. She tries not to interrupt or confer signs of encouragement, pleasure or disapproval. She refrains from asking questions. And, she takes the time to absorb the metaphors, idioms, accompanying gestures, plot and characters involved in the patient’s narrative.

Once her patient has finished with his or her telling, Dr. Charon proceeds to the physical exam portion of the clinical visit. She tries to capture what has been said by writing the story down in her chart while the patient changes into his or her gown and readies for the physical examination.

Dr. Charon writes that it has taken her a while to perfect this form of receiving a patient history. As unorthodox as it may seem, she writes that she has come to thoroughly enjoy the individuality and humanity of the stories that come from each person, each one so different from any other and each belonging to a singular person and body. It has helped her understand her patients, maintain empathy for them and provide them with what she believes is more effective care.

The Parallel Chart

Rita Charon believes that, not only is the use of narrative helpful for the doctor-patient relationship, it can be used to help physicians and other healthcare practitioners digest their experience as well. In one of her years as a clinical supervisor, she developed a practice called the Parallel Chart. As medical students and doctors, we are required to write our patient’s stories in the form of medical charts, following a specific format, creating what can be viewed as an entire literary genre used solely among medical professionals. Medical students and doctors alike are expected to learn to write and maintain a coherent medical chart, according to the standards of this genre.

However, as a clinical supervisor, Rita Charon also has her young precepts write a Parallel Chart, one that will not be filed for reference but that is just for the benefit of the practitioner, written in plain language, about one of his or her patients. She tells her students, “every day you write in the hospital chart about each of your patients. You know exactly what to write there and the form in which to write it. You write about your patient’s current complaints, the results of the physical exam, laboratory findings, opinions of consultants, and the plan. If your patient dying of prostate cancer reminds you of your grandfather, who died of that disease last summer, and each time you go into the patient’s room, you weep for your grandfather, you cannot write that in the hospital chart. We will not let you. And yet it has to be written somewhere. You write it in the Parallel Chart.”

After giving her students these instructions, Rita Charon meets with them in a group once a month and gives everyone the chance to read a Parallel Chart entry of their choice out loud. After the reading, she proceeds to comment on the genre, temporality, metaphors, structure and style of the text that has been written, using her literary background as a guide. The other students then have a chance to respond to the text, creating a dialogue surrounding their clinical experiences.

She reflects that her students in the past have written about their deep attachment to patients, their feelings of helplessness in the clinical encounter in their role as mere medical students, the rage, shame and humiliation they experience in the face of disease as well as their awe at patients’ courage. Dr. Rita Charon claims that the students who undertake the task of keeping a Parallel Chart have found that they are more in touch with their own emotions during the clinical encounter, feel deeper empathy for their patients and fellow colleagues and are able to understand their patients more fully. Research is even being conducted at Columbia University to evaluate the effectiveness of Parallel Charting, finding that physicians who engage in this practice are more proficient and effective at conducting medical interviews, performing medical procedures and developing doctor-patient relationships with patients.

In many ways, naturopathic medicine already acknowledges the importance of patient story-telling when it comes to healing from disease. We treat people as individuals and look for the root cause of illness, taking into account the story behind each of our patient’s “scars”. However, as our school curriculum becomes more medicalized and primary care-focused, I believe that our need to conduct efficient medical interviews and develop effective treatment plans is in danger of displacing our inherent philosophies. Taking the time to read Rita Charon’s book opened my eyes to the importance of patient individuality and respect for patient narrative. To understand illness, it is essential to integrate narrative into the framework of the clinical encounter by giving patients the space to tell, while also giving ourselves, the practitioners, the space for our own telling with the intention of becoming better, more empathetic doctors.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jan 14, 2013 | Art Therapy, Community, Culture, Healing Stories, Health, Music, South America

In Paraguay, South America there is a village, called Cateura, whose main industry is collecting and recycling the waste from the rest of the country. Being from a poor village that acts as Paraguay’s dumping grounds, the citizens of Cateura subsist mainly on sorting and recycling garbage. The documentary Landfill Harmonic, tells the story of Favio Chavez, a music teacher in Cateura, who decided to create a school music program using instruments made entirely of recycled garbage.

(more…)

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Aug 13, 2012 | Art, Art Therapy, Beauty, Body Image, Colour, Creativity, Culture, Finding yourself, Mental Health, Mindfulness, NPLEX, Self-esteem, Self-reflection, Toronto, Writing

My art is mainly inspired by nature or by places I’ve traveled to or read about. It doesn’t tend to emphasize detail and, when humans are included in the composition, they are usually faceless, depicted as chunky, cubist blocks of colour. People are rarely the main subject of my paintings. And, unlike Frida Kahlo, one of my painting idols, I have never entered the world of portrait painting, much less self-portrait painting.

My art is mainly inspired by nature or by places I’ve traveled to or read about. It doesn’t tend to emphasize detail and, when humans are included in the composition, they are usually faceless, depicted as chunky, cubist blocks of colour. People are rarely the main subject of my paintings. And, unlike Frida Kahlo, one of my painting idols, I have never entered the world of portrait painting, much less self-portrait painting.

When painting the facial features of other people, one must pay obsessive attention to detail. This is a skill I don’t have when it comes to painting. It’s almost as if, through painting, I can leave the burden of fussing over details behind to pursue a sense of therapeutic self-pleasing aesthetic that focuses on colour and shape, rather than the fine lines and subtleties. I tend to spend far too much time obsessing over details in real life and so I view painting as an escape from that. When painting life-like portraits, however, such an escape is impossible.

But, like Picasso, I want to become an artist-of-all-trades or, at the very least, claim experience with different subject matter. So, besides feeling that the experience would be tedious and slightly narcissistic, I decided to attempt a self-portrait.

The thing about self-portraits is that we know our own faces very well. From my teenage years through young adulthood I remember countless hours spent obsessing over my reflection: squeezing zits, plucking eyebrows, willing my nose to shrink and wondering what made my face less poetic than that of a famous actress or singer, almost like there was a secret beauty ingredient I might have been born lacking. Painting a self-portrait demands an attention to detail unlike any other mirror flirtation ever performed. From the exact shape of the mouth, to the way the cheeks are outlined, I found myself staring at parts of my reflection that I had never experienced before.

Because I’m not experienced in portrait-painting, the painting started out rough. My oil-painted face was taking on a deformed, misshapen quality, it didn’t look like me, and I found myself criticizing the painting, judging it, and then my own abilities. I then realized, painfully, that this was akin to the way I would criticize my real-life reflection. After a while, though, I found myself comforted by my outline’s familiarity and that comfort turned into a sort of visual satisfaction. This was my face: the window to the person I am who lies beneath and the signature that accompanies everything I say or do in this life. I began to make peace.

Creating art allows us lots of space for reflection. Perhaps that’s why it’s so therapeutic. As I mix colours and apply paint to canvas my mind relaxes and wanders, uninhibited, into new terrain. I find that while painting it helps to have a notebook handy because one artistic pursuit nurtures another and I find myself inspired to not only paint, but write as well. On this portrait-painting day in particular, I felt a relaxing space open up for reflection on who I am now, at 26 years of age. My reflection may have changed some, but behind the wide gaze, I could still see the smirk of that 9-year old, in the Universal Studios sweatshirt, who was imaginative, idealistic and shit-disturbing, all at once. I wonder if this 9-year-old knew that in a few years’ time she would be studying something called naturopathic medicine.

This summer has been dedicated to reviewing basic medical sciences for NPLEX and working as an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher in Toronto. I haven’t made much time for long contemplative walks, reading literature, laying on the grass, socializing or, most of all, painting or drawing. The way I structure my day is a reflection of my disbalance, not my actual interests and priorities and, as I paint, my evolving painted self stares back at me from it’s canvas home and asks me, “is this what you wanted?”

I’m not sure. But portrait painting shows me that there is a link between borderline narcissism and self-contemplation. Maybe that’s why it’s called self-reflection.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jul 23, 2012 | Art Therapy, Balance, Education, Exams, Letting Go, Mental Health, Mindfulness, Motivation, NPLEX, Philosophy, Photography, Preventive Medicine, Stress, Student, Summer, Writing

Like many of my peers I feel like I spend every day eating lunch at the Mandarin buffet – I always seem to have too much on my plate.

Like many of my peers I feel like I spend every day eating lunch at the Mandarin buffet – I always seem to have too much on my plate.

(more…)

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jun 18, 2012 | Art, Art Therapy, Community, Creativity, Culture, Music, Summer Festivals, Theatre Reviews, Urban Living

I am a huge fan of the theatre. With one outlier in mind, there has never been a live performance that I didn’t completely enjoy (the exception happened to be a 3-hour monologue about Simon Bolívar). Every other experience, no matter what the production budget is, has been excellent.

(more…)

It seems like the world is falling apart. These days more than ever.

It seems like the world is falling apart. These days more than ever.