by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Mar 18, 2016 | Balance, Community, Detoxification, Docere, doctor as teacher, Education, Healing Stories, Health, Medicine, Motivation, Narrative Therapy, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Psychology, Self-care, Women's health

People seek out naturopathic doctors for expert advice. This immediately positions us as experts in the context of the therapeutic relationship, establishing a power imbalance right from the first encounter. If left unchecked, this power imbalance will result in the knowledge and experience of the practitioner being preferred to the knowledge, experience, skills and values of the people who seek naturopathic care.

People seek out naturopathic doctors for expert advice. This immediately positions us as experts in the context of the therapeutic relationship, establishing a power imbalance right from the first encounter. If left unchecked, this power imbalance will result in the knowledge and experience of the practitioner being preferred to the knowledge, experience, skills and values of the people who seek naturopathic care.

The implicit expectation of the therapeutic relationship is that it’s up to the doctor to figure out what is “wrong” with the body patients inhabit and make expert recommendations to correct this wrong-ness. After that, it’s up to the patients to follow the recommendations in order to heal. If there is a failure to follow recommendations, it is the patient who has failed to “comply” with treatment. This “failure” results in breakdown of communication, loss of personal agency on the part of the patient, and frustration for both parties.

When speaking of previous experience with naturopathic medicine, patients often express frustration at unrealistic, expensive and time-consuming treatment plans that don’t honour their values and lifestyles. Oftentimes patients express fear at prescriptions that they had no part in creating, blaming them for adverse reactions, or negative turns in health outcomes. It’s common that, rather than address these issues with the practitioner, patients take for granted that the treatment plan offered is the only one available and, for a variety of reasons, choose to discontinue care.

One of the elements of Narrative Therapy—a style of psychotherapy founded by Australian Michael White—I most resonate with is the idea of the “therapeutic posture”. In narrative therapy, the therapist or practitioner assumes a de-centred, but influential posture in the visit. This can be roughly translated as reducing practitioner expertise to that of a guide or facilitator, while keeping the agency, decision-making, expertise and wisdom of the patient as the dominant source for informing clinical decisions. The de-centred clinician guides the patient through questioning, helping to reframe his or her identity by flushing out his or her ideas and values through open-ended questions. However, the interests of the doctor are set aside in the visit.

From the place of de-centred facilitation, no part of the history is assumed without first asking questions, and outcomes are not pursued without requesting patient input. De-centring eschews advice-giving, praise, judgement and applying a normalizing or pathologizing gaze to the patient’s concerns. De-centring the naturopathic practitioner puts the patient’s experiences above professional training, knowledge or expertise. We are often told in naturopathic medical school that patients are the experts on their own bodies. A de-centred therapeutic gaze acknowledges this and uses it to optimize the clinical encounter.

I personally find that in psychotherapy, the applicability of de-centring posture seems feasible—patients expect that the therapist will simply act as a mirror rather than doling out advice. However, in clinical practice, privileging the skills, knowledge and expertise of the patient over those of the doctor seems trickier—after all, people come for answers. At the end of naturopathic clinical encounters, I always find myself reaching for a prescription pad and quickly laying out out my recommendations.

There is an expected power imbalance in doctor-patient relationships that is taught and enforced by medical training. The physician or medical student, under the direction of his or her supervisor, asks questions and compiles a document of notes—the clinical chart. The patient often has little idea of what is being recorded, whether these notes are in their own words, or even if they are an accurate interpretation of what the patient has intended to convey—The Seinfeld episode where Elaine is deemed a “difficult patient” comes to mind when I think of the impact of medical records on people’s lives. After that we make an assessment and prescription by a process that, in many ways, remains invisible to the patient.

De-centred practice involves acknowledging the power differential between practitioner and patient and bringing it to the forefront of the therapeutic interaction.

The ways that this are done must be applied creatively and conscientiously, wherever a power imbalance can be detected. For me this starts with acknowledging payment—I really appreciate it when my patients openly tell me that they struggle to afford me. There may not be something I can do about this, but if I don’t know the reason for my patient falling off the radar or frequently cancelling when their appointment time draws near, there is certainly nothing I can do to address the issue of cost and finances. Rather than being a problem separate from our relationship, it becomes internal the the naturopathic consultation, which means that solutions can be reached by acts of collaboration, drawing on the strengths, knowledge and experience of both of us.

In a similar vein, addressing the intersection of personal finance and real estate within the therapeutic relationship requires a delicate balance of empathy and practicality. Patients may be navigating the complexities of homeownership or rental expenses, which can significantly impact their overall well-being. Encouraging open communication about these financial stressors fosters an environment where solutions can be explored collaboratively. It’s essential to recognize that financial challenges are not isolated issues but are intricately woven into the fabric of a person’s life, influencing mental and emotional well-being.

For instance, a patient might express concerns about the financial strain associated with homeownership, prompting a discussion about alternative housing options or budgeting strategies. In this context, exploring unconventional opportunities, such as innovative approaches to real estate like eXp Realty, could naturally arise. Integrating discussions about progressive real estate models within the therapeutic dialogue allows for a holistic exploration of solutions, leveraging the expertise and experiences of both the practitioner and the patient. This approach not only addresses immediate concerns but also lays the foundation for a collaborative and conscientious partnership in navigating the multifaceted aspects of personal finance and real estate.

De-centred practice involves practicing non-judgement and removing assumptions about the impact of certain conditions. A patient may smoke, self-harm or engage in addictive behaviours that appear counterproductive to healing. It’s always useful to ask them how they feel about these practices—these behaviours may be hidden life-lines keeping patients afloat, or gateways to stories of very “healthy” behaviours. They may be clues to hidden strengths. By applying a judgemental, correctional gaze to behaviours, we can drive a wedge in the trust and rapport between doctor and patient, and the potential to uncover and draw on these strengths for healing will be lost.

De-centred practice involves avoiding labelling our patients. A patient may not present with “Generalized Anxiety Disorder”, but “nervousness” or “uneasiness”, “a pinball machine in my chest” or, one of my favourites, a “black smog feeling”. It’s important to be mindful about adding a new or different labels and the impact this can have on power and identity. We often describe physiological phenomena in ways that many people haven’t heard before: estrogen dominance, adrenal fatigue, leaky gut syndrome, chronic inflammation. In our professional experience, these labels can provide relief for people who have suffered for years without knowing what’s off. Learning that something pathological is indeed happening in the body, that this thing has a name, isn’t merely a figment of the imagination and, better still, has a treatment (by way of having a name), can provide immense relief. However, others may feel that they are being trapped in a diagnosis. We’re praised for landing a “correct” diagnosis in medical school, as if finding the right word to slap our patients with validates our professional aptitude. However, being aware of the extent to which labels help or hinder our patients capacities for healing is important for establishing trust.

To be safe, it can help to simply ask, “So, you’ve been told you have ‘Social Anxiety’. What do you think of this label? Has it helped to add meaning to your experience? Is there anything else you’d like to call this thing that’s been going on with you?”

Avoiding labelling also includes holding back from using the other labels we may be tempted to apply such as “non-compliant”, “resistant”, “difficult”, or to group patients with the same condition into categories of behaviour and identity.

It is important to attempt to bring transparency to all parts of the therapeutic encounter, such as history-taking, physical exams, labs, charting, assessment and prescribing, whenever possible. I’ve heard of practitioners reading back to people what they have written in the chart, to make sure their recordings are accurate, and letting patients read their charts over to proofread them before they are signed. The significance of a file existing in the world about someone that they have never seen or had input into the creation of can be quite impactful, especially for those who have a rich medical history. One practitioner asks “What’s it like to carry this chart around all your life?” to new patients who present with phonebook-sized medical charts. She may also ask, “Of all the things written in here about you, what would you most like me to know?” This de-emphasizes the importance of expert communication and puts the patient’s history back under their own control.

Enrolling patients in their own treatment plan is essential for compliance and positive clinical outcomes. I believe that the extent to which a treatment plan can match a patient’s values, abilities, lifestyle and personal preferences dictates the success of that plan. Most people have some ideas about healthy living and natural health that they have acquired through self-study, consuming media, trial-and-error on their own bodies or consulting other healthcare professionals. Many people who seek a naturopathic doctor are not doing so for the first time and, in the majority of cases, the naturopathic doctor is not the first professional the patient may have consulted. This is also certainly not the first time that the person has taken steps toward healing—learning about those first few, or many, steps is a great way to begin an empowering and informed conversation about the patients’ healing journey before they met you. If visiting a naturopathic doctor is viewed as one more step of furthering self-care and self-healing, then the possibilities for collaboration become clearer. Many people who see me have been trying their own self-prescriptions for years and now finally “need some support” to help guide further action. Why not mobilize the patient’s past experiences, steps and actions that they’ve already taken to heal themselves? Patients are a wealth of skills, knowledge, values, experiences and beliefs that contribute to their ability to heal. The vast majority have had to call on these skills in the past and have rich histories of using these skills in self-healing that can be drawn upon for treatment success.

De-centring ourselves, at least by a few degrees, from the position of expertise, knowledge and power in the therapeutic relationship, if essential for allowing our patients to heal. A mentor once wrote to me, “Trust is everything. People trust you and then they use that trust to heal themselves.”

By lowering our status as experts, we increase the possibility to build this trust—not just our patients’ trust in our abilities as practitioners, but patients’ trust in their own skills, knowledge and abilities as self-healing entities. I believe that de-centring practitioner power can lead to increased “compliance”, more engagement in the therapeutic treatment, more opportunities for collaboration, communication and transparency. It can decrease the amount of people that discontinue care. I also believe that this takes off the burden of control and power off of ourselves—we aren’t solely responsible for having the answers—decreasing physician burnout. Through de-centring, patients and doctors work together to come up with a solution that suits both, becoming willing partners in creating treatment plans, engaging each other in healing and thereby increasing the trust patients have in their own bodies and those bodies’ abilities to heal.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Mar 14, 2016 | Asian Medicine, Balance, Creativity, Culture, Happiness, Health, Meditation, Mental Health, Mind Body Medicine, Mindfulness, Naturopathic Philosophy, Philosophy, Psychology, Stress

When a successful person is asked to share the secrets of his or her success, the unanimous response is that success requires “effort” and “hard work”. Other popular euphemisms are that success demands “sweat, blood and tears” or “1% inspiration, 99% perspiration”. In grade school we’re lectured on working harder and reprimanded for not trying hard enough. Put in the time and effort to get the grades that will land you the job that will require similar or increasing levels of time and effort. Olympic athletes are lauded as modern-day heroes for their early mornings, punishing workouts and restricted diets. Our society reveres those who put in 80-hour work weeks, despite their implausibility, as we all need to sleep, eat and defecate, which take up hours that are obviously not spent working. It’s a shame to some that we’re limited by these earthly, time-consuming bodies that have been the disdain of capitalism since it’s inception. I see more youth in my practice, who are already bearing the weight of society’s expectations. They are working hard, as instructed, and this “hard work” is taking a physical, mental and emotional toll on their lives. But what can they do? Success requires effort, goes the mantra of our times.

When a successful person is asked to share the secrets of his or her success, the unanimous response is that success requires “effort” and “hard work”. Other popular euphemisms are that success demands “sweat, blood and tears” or “1% inspiration, 99% perspiration”. In grade school we’re lectured on working harder and reprimanded for not trying hard enough. Put in the time and effort to get the grades that will land you the job that will require similar or increasing levels of time and effort. Olympic athletes are lauded as modern-day heroes for their early mornings, punishing workouts and restricted diets. Our society reveres those who put in 80-hour work weeks, despite their implausibility, as we all need to sleep, eat and defecate, which take up hours that are obviously not spent working. It’s a shame to some that we’re limited by these earthly, time-consuming bodies that have been the disdain of capitalism since it’s inception. I see more youth in my practice, who are already bearing the weight of society’s expectations. They are working hard, as instructed, and this “hard work” is taking a physical, mental and emotional toll on their lives. But what can they do? Success requires effort, goes the mantra of our times.

This effort shows up on faces and in bodies. Our minds exhaust us with chastising inner talk; teeth clench, jaws grind and shoulders hunch around ears, creating a new neck-less species, The Hard Worker, inhabiting the earth in increasing numbers.

70% of people today admit to being under stress. When I asked my patients if they feel “stressed”, many shrug, deny or tell me their stress is nothing that they can’t handle, and then proceed to rank their stress levels as 6 out of 10 or higher, 10 being a hair-pulling, crazy-eyed, stressed-out-of-their-wits state—I find it significant that being more than halfway to our limits still qualifies us as not being stressed.

It’s likely that admitting to stress and overwhelm is a weakness in our effort-driven society. If the bodies we inhabit fail to perform, we’ll be replaced by someone more able-bodied, or someone more able or willing to push their limits and sacrifice their health for short-term success—or maybe a machine. Machines don’t need paid vacation or sick leave. While the future seems bleak, it certainly helps with the healing business, as 75-90% of doctor’s visits are either directly or indirectly stress-related. We know that stress has the power to wreck havoc on the body, contributing to diseases, inflammation, decreased immunity, proliferation of cancer and premature aging. We know that stress is implicated in the rising incidence of mental health conditions. We know that things can’t go on as they are, the system is simply not working.

And so when modern society is failing us, it helps to turn to ancient ideas, before it all went wrong, such as Taoist philosophy, to look for answers. The Taoist principles of wu wei, or “effortless action”, tell us that action does not always originate from effort and stress. Effective actions, like creativity and good ideas, can occur spontaneously and of their own accord.

In a society where relentless growth and production are imperative for the survival of the economy, it’s hard to image any action in the absence of sheer effort. Incessant production can’t rely on the eb and flow cycles of natural inspiration and creativity to dictate when, how much or how hard we work. And yet, this perhaps says more about the societal necessities of the work available to us, and our enjoyment (or lack thereof) of such work, than it does about human inspiration. I’ve been planning this blogpost for a while and although it might have been written sooner if set to a deadline, I’ve eventually gotten around to it; here it is. It is a fact that when things need to get done, they will. The doing might happen later than we’d like it to, and yet it still happens, inspired by a genuine desire or necessity, rather than pressure-cooker of stress.

I’m often asked, as a doctor, to help support my patients’ bodies in periods of intense stress—”periods” that have gone on for years with no apparent end in sight. While there are several remedies that can help the body recuperate from the wear and tear of effort or help the adrenal glands secrete more cortisol to continue producing more and faster, there’s also only so much that can be squeezed out of tired organs. Oftentimes, as I’ve written before, the path to healing is paved with introspection and a serious reconsideration of lifestyle. Can we continue to produce and strive at our current rates and still expect to feel fit, healthy and energized? We can build faster computers and smarter phones but our bodies are very much limited to the tools nature has slowly evolved over time, including the natural medicines available to us. Perhaps our lifestyles, like the economy and the stress on the environment, are simply unsustainable. Perhaps it’s time to question how many of the activities in our lives are worth the effort.

While it may not be possible to quit our jobs, pack up and move to the Bahamas, perhaps there are small nooks in our routines where wu wei might fit and flourish. It may be possible to ease up on our own expectations of ourselves, or give up some of our conventional ideas of success. After all, is the journey to success worth slogging if we won’t be happy or healthy when we get there? Finding space in our lives to allow action to arise spontaneously may be crucial in doing the necessary, healing work of stress-management.

Applying wu wei might mean examining the intentions behind our actions and our current lifestyles. Here are some questions to ask yourself.

- When is effort appropriate and when is it wasted?

- Where am I trying to get to? What is my definition of success?

- Is there a day/afternoon/hour in my week when I can “schedule” unscheduled time?

- Are there tasks I can ease up on, laundry for instance, that I can trust will get done on their own time?

- Can I agree to forgive myself when I fail to meet deadlines or choose to take a day off?

- What would it feel like to stop paddling and let the current carry me for a while? Can I do this at work? At home?

- In what area of my life could I allow myself a little more room to breathe?

- What are my top ten values in life? What goals align with those values? What actions would help me move closer to those goals? How much does thinking of those actions excite or inspire me?

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Feb 23, 2016 | Art, Art Therapy, Balance, Culture, Digestion, Docere, Education, Emotions, Finding yourself, Happiness, Healing Stories, Health, Letting Go, Lifestyle, Listening, Love, Medicine, Meditation, Mental Health, Mind Body Medicine, Mindfulness, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Patience, Philosophy, Psychology, Reflections, Self-care, Self-reflection

Today, I’m 30, working on my career as a self-employed health professional and a small business owner and living on my own. I’ve moved through a lot of states, emotions and life experiences this year, which has been appropriate for closing the chapter on my 20’s and moving into a new decade of life. I’ve experienced huge changes in the past year and significant personal growth thanks to the work I’ve been blessed to do and the people who have impacted me throughout the last 30 years. Here are 30 things this past year has taught me.

Today, I’m 30, working on my career as a self-employed health professional and a small business owner and living on my own. I’ve moved through a lot of states, emotions and life experiences this year, which has been appropriate for closing the chapter on my 20’s and moving into a new decade of life. I’ve experienced huge changes in the past year and significant personal growth thanks to the work I’ve been blessed to do and the people who have impacted me throughout the last 30 years. Here are 30 things this past year has taught me.

- Take care of your gut and it will take care of you. It will also eliminate the need for painkillers, antidepressants, skincare products, creams, many cosmetic surgeries, shampoo and a myriad of supplements and products.

- Trying too hard might not be the recipe for success. In Taoism, the art of wu wei, or separating action from effort might be key in moving forward with your goals and enjoying life; You’re not falling behind in life. Additionally, Facebook, the scale and your wallet are horrible measures to gauge how you’re doing in life. Find other measures.

- If you have a chance to, start your own business. Building a business forces you to build independence, autonomy, self-confidence, healthy boundaries, a stronger ego, humility and character, presence, guts and strength, among other things. It asks you to define yourself, write your own life story, rewrite your own success story and create a thorough and authentic understanding of what “success” means to you. Creating your own career allows you to create your own schedule, philosophy for living and, essentially, your own life.

- There is such as thing as being ready. You can push people to do what you want, but if they’re not ready, it’s best to send them on their way, wherever their “way” may be. Respecting readiness and lack thereof in others has helped me overcome a lot of psychological hurdles and avoid taking rejection personally. It’s helped me accept the fact that we’re all on our own paths and recognize my limitations as a healer and friend.

- Letting go is one of the most important life skills for happiness. So is learning to say no.

- The law of F$%3 Yes or No is a great rule to follow, especially if you’re ambivalent about an impending choice. Not a F— Yes? Then, no. Saying no might make you feel guilty, but when the choice is between feeling guilty and feeling resentment, choose guilt every time. Feeling guilty is the first sign that you’re taking care of yourself.

- Patience is necessary. Be patient for your patients.

- Things may come and things may go, including various stressors and health challenges, but I will probably always need to take B-vitamins, magnesium and fish oil daily.

- Quick fixes work temporarily, but whatever was originally broken tends to break again. This goes for diets, exercise regimes, intense meditation practices, etc. Slow and steady may be less glamorous and dramatic, but it’s the only real way to change and the only way to heal.

- When in doubt, read. The best teachers and some of the best friends are books. Through books we can access the deepest insights humanity has ever seen.

- If the benefits don’t outweigh the sacrifice, you’ll never give up dairy, coffee, wine, sugar and bread for the long term. That’s probably perfectly ok. Let it go.

- Patients trust you and then they heal themselves. You learn to trust yourself, and then your patients heal. Developing self-trust is the best continuing education endeavour you can do as a doctor.

- Self-care is not selfish. In fact, it is the single most powerful tool you have for transforming the world.

- Why would anyone want to anything other than a healer or an artist?

- Getting rid of excess things can be far more healing than retail therapy. Tidying up can in fact be magical and life-changing.

- It is probably impossible to be truly healthy without some form of mindfulness or meditation in this day and age.

- As Virginia Woolf once wrote, every woman needs a Room of Own’s Own. Spending time alone, with yourself, in nature is when true happiness can manifest. Living alone is a wonderful skill most women should have—we tend to outlive the men in our lives, for one thing. And then we’re left with ourselves in the end anyways.

- The inner self is like a garden. We can plant the seeds and nurture the soil, but we can’t force the garden to grow any faster. Nurture your garden of self-love, knowledge, intuition, business success, and have faith that you’ll have a beautiful, full garden come spring.

- Be cheap when it comes to spending money on everything, except when it comes to food, travel and education. Splurge on those things, if you can.

- Your body is amazing. Every day it spends thousands of units of energy on keeping you alive, active and healthy. Treat it well and, please, only say the nicest things to it. It can hear you.

- If you’re in a job or life where you’re happy “making time go by quickly”, maybe you should think of making a change. There is only one February 23rd, 2016. Be grateful for time creeping by slowly. When you can, savour the seconds.

- Do no harm is a complicated doctrine to truly follow. It helps to start with yourself.

- Drink water. Tired? Sore? Poor digestion? Weight gain? Hungry? Feeling empty? Generally feeling off? Start with drinking water.

- Do what you love and you’ll never have to work a day in your life. As long as what you love requires no board exams, marketing, emailing, faxing, charting, and paying exorbitant fees. But, since most careers have at least some of those things, it’s still probably still preferable to be doing something you love.

- Not sure what to do? Pause, count to 7, breathe. As a good friend and colleague recently wrote to me, “I was doing some deep breathing yesterday and I felt so good.” Amen to that.

- As it turns out, joining a group of women to paint, eat chocolate and drink wine every Wednesday for two months can be an effective form of “marketing”. Who knew?

- “Everyone you meet is a teacher”, is a great way to look at online dating, friendships and patient experiences. Our relationships are the sharpest mirrors through which we can look at ourselves. Let’s use them and look closely.

- Being in a state of curiosity is one of the most healing states to be in. When we look with curiosity, we are unable to feel judgment, anxiety, or obsess about control. Curiosity is the gateway to empathy and connection.

- Aiming to be liked by everyone prevents us from feeling truly connected to the people around us. The more we show up as our flawed, messy, sometimes obnoxious selves, the fewer people might like us. However, the ones who stick around happen to love the hot, obnoxious mess they see. As your social circle tightens, it will also strengthen.

- If everyone is faking it until they make it, then is everyone who’s “made” it really faking it? These are the things I wonder while I lie awake at night.

Happy Birthday to me and happy February 23rd, 2016 to all of you!

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jan 29, 2016 | Healing Stories, Health, Medicine, Meditation, Mental Health, Mind Body Medicine, Mindfulness, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Philosophy, Self-care, Self-reflection, Stress

I’ve come to see my migraines as an internal measuring device for wellness, or rather, lack of wellness—kind of like a very painful meat thermometer. From time to time I get bouts of low energy compelling me to spend more time doing low-key activities. However, quick browses through Facebook show me busy colleagues achieving great things and I feel guilty about my relative inaction. A little voice pipes up. “Your body is telling you to rest”, it says. “But if you just started doing things, you’d probably feel more motivation”, voices another, its opponent, the devil on my shoulder. A war ensues and then a headache settles it all. I take it easy for a while, while I’m literally knocked out of commission, in the dark, on the couch with an icepack on my head.

L came to me for fertility, which is another litmus test for good health. When the body is struggling against some sort of imbalance or obstacle to wellness, it will not spend its resources readying eggs, ovulating and ripening uteruses. Our bodies protect us from the metabolic demands of having a pregnancy, which in our current stressed-out, unwell states we probably wouldn’t be able to handle, by simply not getting pregnant in the first place. And so, infertility is a nice entry-way to healing—patients are motivated to examine the effect of their lifestyles on their wellbeing.

The problem was, however, that L barely had time to make and attend her appointments. When she did manage to come in, she was in a rush. She’d often cancel follow-ups because she hadn’t followed through with the previous visit’s plan, even though it had been weeks before. She also reported working 50-hour weeks and staying up early into the morning to work on projects. I wondered, if she couldn’t even make an hour-long appointment with her naturopathic doctor, how would she manage growing and then giving birth to and then raising a brand new human? L simply might have not been ready to heal. Something in me fought to give her my professional assessment; in order to have the baby she wanted, she might have to give up, or significantly let up on, the demands of her job. However, how could I have made such a statement? I held my tongue and tried my best with the modalities at my disposal. We did acupuncture, CoQ10, PQQ and herbal remedies. We worked on sleep and did stress management with adaptogens. In a few months, despite the high demands of her lifestyle, L was pregnant. She still has trouble keeping her appointments with me. L’s body may now be functioning fine, but is it thriving?

Workplace wellness programs teach employees how to survive the 60+ hour workweeks in the office by doing yoga at lunch and eating healthier cafeteria food. They’re taught about stress management and, in the best of cases, given adaptogens and B-vitamins to help their bodies’ sails weather the stress-intensive storms of office life. It’s a great investment, these programs proclaim, because employees are happier, more efficient at their work and take less sick days. Workplace wellness programs keep their employees functional but, I wonder, can anyone really be well working that many hours a week?

When it comes to the health strategies we promote as a profession, how many of them are geared towards healing and how many of them are really just there to help us function?

At this stage in my career, I often have to gauge what my patients want. There are some people who come in ready to heal. They want to search for and address the real root cause of disease, no matter how elusive it may be. They are also willing to do what it takes to get better, even if it means a significant lifestyle shift. Sometimes these patients are at a point where things have gotten so bad that they have no other choice, however some of them simply intuit that the symptoms arising may be conveying a greater message; in order to be truly healthy, things might have to change. Most patients, however, come in looking to “feel better”—they simply want their symptoms to go away so they can get back to their daily lives, lives that might have made them sick in the first place. In our pharmaceutical-based Therapeutics and Prescribing exam, the goal of therapy in the oral cases was always to “restore functioning”, as if our patients were simply pieces of machinery; our parts are worn, maybe broken and we’ve gone decades without a decent oil change, but the factory declares we must get back to work as soon as possible and so we break out the duct tape. With this mindset, however, are we simply placating our bodies long enough to keep working until we eventually succumb to the next thing, a debilitating headache instead of mild fatigue, or something even worse? How long can we go suppressing symptoms or getting our bodies into decent enough shape before we realize that what we really need is some honest-to-goodness authentic healing?

Jiddu Krishnamurti, Hindu philosopher and teacher once said, “It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” How much of our health marketing and wellness efforts are aimed at cleaning out the cogs in a jammed up machine so that they can go on turning smoothly again? The thought that real healing might mean dismantling the entire machine might be too radical for our society to handle. How can we address the problem of making a living if we acknowledge the fact that our lifestyle, or job, might be making us sick?

A therapist I work with (doctors need healing too!) once told me that mild to moderate depression is a sign that something in your life needs changing. “Look at the symptoms of depression,” She told me one afternoon in her office, “You lose the energy and motivation to keep going with your routine. You stop being social; all of your energy turns inwards. You focus your attention on your self and your life so that you can examine what about it is making you unhappy. Then you change it.” Then you change it, a scary thought. No wonder a tenth of the population opts for anti-depressant medication, which in some cases might be the medical equivalent of dusting oneself off and heading back to work. And, while they seem like more benign options, St. John’s Wort, B12 injections and 5HTP may not be that different.

A friend and I were talking about this very topic. He remarked that at a fitness retail store he worked at he’d often ask his female customers, “What will you be needing these yoga pants for today: form or function?” When I laughed at the shallowness of it all, he protested, “Well, some people are just going to use them to sit in coffee shops while others want to actually work out. What’s going to make your butt look great won’t necessarily be the best choice at the gym. I had to know their motivations.” Are most of our wellness efforts aimed at making our butts look great or are they filling a functional purpose?

I wonder if I should follow my friend’s lead and outright ask my patients, maybe on their intake forms, “Are you looking to truly heal today or do you just want to feel better and get back to work?”—form or function? Being candid with them, might help me decide when to schedule follow-up appointments. At any rate, it would definitely open up a conversation about expectations surrounding decent time-frames for seeing “results” and what true healing might look like for them. The trouble is, restoring functioning, if not easier, is more straight-forward. You make some tweaks to diet, correct some nutritional deficiencies and boost the adrenals or liver. It’s the medical equivalent of filling in potholes with cheap cement—it might not look pretty, but now you can drive on it. Healing, however, is more complex. It’s more convoluted, hard to define and get a firm grasp on. It is also highly individual. It might mean ripping up the entire road, plumbing and all, and building a new one or, even better, planting grass and flowers in the road’s place and nurturing that grass on a daily basis. Healing might be creating something entirely new, something that no one has ever heard of or seen before. Creating is scary. Creativity takes courage, and so does healing.

No matter what it might look like, I believe healing begins with a conversation and a willingness to look inwards, without judgement. Healing also requires an acceptance of what is, even if the individual doesn’t feel ready to take actions to heal just yet. Healing deserves us acknowledging that something is a band-aid solution. Healing definitely demands listening, especially to the body. Therefore, healing might begin in meditation. It might start with a mind-searing migraine that lands you on the couch and the thought, “What if, instead of reaching for the Advil, I just rested a little bit today?” Healing might just start there and it might never end. But, if it does, who knows where it might end up?

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jan 7, 2016 | Asian Medicine, Book, Book Review, Diet, Docere, Education, Evidence Based Medicine, Exams, Healing Stories, Health, Medicine, Narrative Therapy, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Philosophy

A singular narrative is told and retold regarding medicine in the west. The story goes roughly like this: the brightest students are accepted into medical schools where they learn—mainly through memorization—anatomy, physiology, pathology, diagnostics, microbiology, and the other “ologies” to do with the human physique. They then become doctors. These doctors then choose a specialty, often associated with a specific organ system (dermatology) or group of people (pediatrics), who they will concentrate their knowledge on. The majority of the study that these doctors undergo concerns itself with establishing a diagnosis, i.e.: producing a label, for the patient’s condition. Once a diagnosis has been established, selecting a treatment becomes standardized, outlined often in a cookbook-like approach through guidelines that have been established by fellow doctors and pharmaceutical research.

A singular narrative is told and retold regarding medicine in the west. The story goes roughly like this: the brightest students are accepted into medical schools where they learn—mainly through memorization—anatomy, physiology, pathology, diagnostics, microbiology, and the other “ologies” to do with the human physique. They then become doctors. These doctors then choose a specialty, often associated with a specific organ system (dermatology) or group of people (pediatrics), who they will concentrate their knowledge on. The majority of the study that these doctors undergo concerns itself with establishing a diagnosis, i.e.: producing a label, for the patient’s condition. Once a diagnosis has been established, selecting a treatment becomes standardized, outlined often in a cookbook-like approach through guidelines that have been established by fellow doctors and pharmaceutical research.

The treatment that conventional doctors prescribe has its own single story line involving substances, “drugs”, that powerfully over-ride the natural physiology of the body. These substances alter the body’s processes to make them “behave” in acceptable ways: is the body sending pain signals? Shut them down. Acid from the stomach creeping into the esophagus? Turn off the acid. The effectiveness of such drugs are tested against identified variables, such as placebo, to establish a cause and effect relationship between the drug and the result it produces in people. Oftentimes the drug doesn’t work and then a new one must be tried. Sometimes several drugs are tried at once. Some people get better. Some do not. When the list is exhausted, or a diagnosis cannot be established, people are chucked from the system. This is often where the story ends. Oftentimes the ending is not a happy one.

On July 1st, naturopathic doctors moved under the Regulated Health Professionals Act in the province of Ontario. We received the right to put “doctor” on our websites and to order labs without a physician signing off on them. However, we lost the right to inject, prescribe vitamin D over 1000 IU and other mainstay therapies we’d been trained in and been practicing safely for years, without submitting to a prescribing exam by the Canadian Pharmacists Association. Naturopathic doctors could not sit at the table with the other regulated health professions in the province until we proved we could reproduce the dominant story of western medicine—this test would ensure we had.

Never mind that this dominant story wasn’t a story about our lives or the medicine we practice—nowhere in the pages of the texts we were to read was the word “heal” mentioned. Nowhere in those pages was there an acknowledgement about the philosophy of our own medicine, a respect towards the body’s own self-healing mechanisms and the role nature has to play in facilitating that healing process. It was irrelevant that the vast majority of this story left out our years of clinical experience. The fact that we already knew a large part of the dominant story, as do the majority of the public, was set aside as well. We were to take a prescribing course and learn how primary care doctors (general practitioners, family doctors and pediatricians), prescribe drugs. We were to read accounts of the “ineffectiveness” of our own therapies in the pages of this narrative. This would heavy-handedly dismiss the experience of the millions of people around the world who turn to alternative medicine every year and experience success.

We were assured that there were no direct biases or conflict of interests (no one was directly being paid by the companies who manufacture these drugs). However, we forget that to have one story is to be inherently and dangerously biased. Whatever the dominant story is, it strongly implies that there is one “truth” that it is known and that it is possessed by the people who tell and retell it. Other stories are silenced. (Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie describes this phenomenon in her compelling TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story”).

Despite the time and money it cost me, taking the prescribing course afforded me an opportunity to step outside of the discouraging, dominant story of the standard medical model and thicken the subordinate stories that permeate the natural and alternative healing modalities. These stories began thousands of years ago, in India and in China, at the very root of medicine itself. They have formed native ancestral traditions and kept entire populations and societies alive and thriving for millennia. Because our stories are not being told as often, or told in the context of “second options” or “last resorts”, when the dominant narratives seem to fail us, the people who tell them run the risk of being marginalized or labeled “pseudoscientific.” These dismissals, however, tell us less about The Truth and more about the rigid simplicity of the singular story of the medical model.

It is frightening to fathom that our body, a product of nature itself, encompasses mysteries that are possibly beyond the realm of our capacity for understanding. It’s horrifying to stand in a place of acknowledgement of our own lack of power against nature, at the inevitability of our own mortality. However, if we refuse to acknowledge these truths, we close ourselves off to entire systems that can teach us to truly heal ourselves, to work with the body’s wisdom and to embrace the forces of nature that surround us. The stories that follow are not capital T truths, however, they can enrich the singular story that we in the west have perpetuated for so long surrounding healing.

The body cannot be separated into systems. Rather than separating depression and diarrhea into psychiatry and gastroenterology, respectively, natural medicine acknowledges the interconnectivity between the body’s systems, none of which exist in a vacuum. When one system is artificially manipulated, others are affected. Likewise, an illness in one system may result in symptoms in another. There have been years of documentation about the gut-brain connection, which the medical model has largely ignored when it comes to treatment. The body’s processes are intricately woven together; tug on one loose thread and the rest either tightens or unravels.

We, as products of nature, may never achieve dominion over it. Pharmaceutical drugs powerfully alter the body’s natural physiology, often overriding it. Since these drugs are largely manmade, isolated from whole plants or synthesized in a lab, they are not compounds found naturally. Despite massive advances in science, there are oceans of what we don’t know. Many of these things fit into the realm of “we don’t know what we don’t know”—we lack the knowledge sufficient to even ask the right questions. Perhaps we are too complex to ever truly understand how we are made. Ian Stewart once wrote, “If our brains were simple enough for us to understand them, then we’d be so simple that we couldn’t.” And yet, accepting this fact, we synthesize chemicals that alter single neurotransmitters, disrupting our brain chemistry, based on our assumption that some people are born in need of “correcting” and we have knowledge of how to go about this corrective process. Such is the arrogance of the medical model.

There are always more than two variables in stories of disease and yet the best studies, the studies that dictate our knowledge, are done with two variables: the drug and its measured outcome. Does acetaminophen decrease pain in patients with arthritis when compared to placebo? A criticism of studies involving natural medicine is that there are too many variables—more than one substance is prescribed, the therapeutic relationship and lifestyle changes exert other effects, a population of patients who value their health are different than those who do not, the clinical experience is more attentive, and so on. With so many things going on, how can we ever know what is producing the effect? However, medicine is limited in effect if we restrict ourselves to the prescription of just one thing. This true in herbalism, where synergy in whole plants offers a greater effect than the sum of their isolated parts. By isolating a single compound from a plant, science shows us that we may miss out on powerful healing effects. Like us, plants have evolved to survive and thrive in nature; their DNA contains wisdom of its own. Stripping the plant down to one chemical is like diluting all of humanity down to a kidney. There is a complexity to nature that we may never understand with our single-minded blinders on.

Studies are conducted over the periods of weeks and, rarely, months, but very rarely are studies done over years or lifetimes. Therefore, we often look for fast results more than signs of healing. This is unfortunate because, just as it takes time to get sick, it takes time to heal. I repeat the previous sentence like a mantra so patients who have been indoctrinated into a medical system that produces rapid results can reset expectations about how soon they will see changes. Sometimes a Band-Aid is an acceptable therapy; few of us can take long, hard looks at our lives and begin an often painful journey in uncovering what hidden thought process or lifestyle choices may be contributing to the symptoms we’re experiencing. However, the option of real healing should be offered to those who are ready and willing.

When we study large masses of people, we forget about individuality. When we start at the grassroots level working with patients on the individual level, we familiarize ourselves with their stories, what healing means to them. In science, large studies are favoured over small ones. However, in studies of thousands of people, singular voices and experiences are drowned out. We lose the eccentric individualities of each person, their genetic variability, their personalities, their preferences and their past experiences. We realize that not everyone fits into a diagnostic category and yet still suffers. We realize that not everyone gets better with the standard treatments and the standard dosages. Starting at the level of the individual enables a clinician to search for methods and treatments and protocols that benefit each patient, rather than fitting individuals into a top-down approach that leaves many people left out of the system to suffer in silence.

It is important to ask the question, “why is this happening?” The root cause of disease, which naturopathic medicine claims to treat is not always evident and sometimes not always treatable. However, the willingness to ask the question and manipulate the circumstances that led to illness in the first place is the first step to true and lasting healing; everything else is merely a band-aid solution, potentially weakening the body’s vitality over time. No drug or medical intervention is a worthy substitute for clean air, fresh abundant water, nutritious food, fulfilling work and social relationships, a connection to a higher purpose, power or philosophy and, of course, good old regular movement. The framework for good health must be established before anything else can hope to have an effect.

The system of naturopathic medicine parallels in many ways the system of conventional pharmaceutical-based medicine. We both value science, we both strive to understand what we can about the body and we value knowledge unpolluted by confusing variables or half-truths. However, there are stark differences in the healing philosophies that can’t be compared. These differences strengthen us and provide patients with choice, rather than threatening the establishment. The time spent with patients, the principles of aiming for healing the root cause and working with individuals, rather than large groups, offer a complement to a system that often leaves people out.

There are as many stories of healing and medicine as there are patients. Anyone who has ever consulted a healthcare practitioner, taken a medicine or soothed a cold with lemon and honey, has experienced some kind of healing and has begun to form a narrative about their experience. Anyone with a body has an experience of illness, healing or having been healed. Those of us who practice medicine have our own experience about what works, what heals and what science and tradition can offer us in the practice of our work. Medicine contains in its vessel millions of stories: stories of doubt, hopelessness, healing, practitioner burnout, cruises paid for my pharmaceutical companies, scientific studies, bias, miracle cures, promise, hope and, most of all, a desire to enrich knowledge and uncover truth. Through collecting these stories and honouring each one of them as little truth droplets in the greater ocean of understanding, we will be able to deepen our appreciation for the mystery of the bodies we inhabit, learn how to thrive within them and understand how to help those who suffer inside of them, preferably not in silence.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Nov 16, 2015 | doctor as teacher, Education, Emotions, Endocrinology, Healing Stories, Hormones, Listening, Medicine, Meditation, Mind Body Medicine, Naturopathic Philosophy, Preventive Medicine, Reflections, Women's health, Writing

Premature Ovarian Failure no longer bears that name. It’s not a failure anymore, but an insufficiency. POF becomes POI: Premature Ovarian Insufficiency, as insufficiency is apparently a softer term than “failure”. For me, it’s another telling example of how our society fears the names of things, and twists itself into knots of nomenclature and terminology rather than facing pain head-on. In this case, the pain is derived from the simple fact that the ovaries do not respond to hormones, that they for some reason die at an early age and cause menopause to arrive decades before it’s due, leading to infertility and risk of early osteoporosis.

Insufficiency, for me at least, fails to appease the sensitivity required for naming a problem. It reminds me of a three-tiered scoring system: exceeds expectations, meets expectations, insufficient performance. These reproductive cells have not been up to task. They’ve proven to be insufficient and, in the end, we’ve labelled them failures anyway—premature ovarian disappointments. Our disdain for the bodies we inhabit often becomes apparent in medical jargon.

What expectations do we have for our organs, really? For most of us that they’ll keep quiet while we drink, stay up late and eat what we like, not that they will protest, stop our periods, make us itch or remind us that we are physical beings that belong here, to this earth, that we can sputter and shut down and end up curb side while we wait for white coats to assist us. Our organs are not supposed to remind us of our fragile mortality. When it comes to expectations overall, I wonder how many of them we have a right to.

In one week I had two patients presenting with failures of sorts. With one it was her ovaries, in another it was his kidneys, first his left, now his right. Both of them were coming to me, perhaps years too late, for a style of medicine whose power lies mainly in prevention or in stopping the ball rolling down the hill before it gains momentum. When disease processes have reached their endpoint, when there is talk of transplant lists and freezing eggs, I wonder what more herbs can do.

And so, when organs fail, I fear that I will too.

In times of failure, we often lose hope. However, my patients who have booked appointments embody a hope I do not feel myself, a hope I slightly resent. In hope there is vulnerability, there is an implicit cry for help, a trust. These patients are paying me to “give them a second opinion”, they say, or a “second truth”.

I feel frustration bubble to the surface when I pore over the information I need to manage their cases. At the medical system: “why couldn’t they give these patients a straight answer? Why don’t we have more information to help them?” At my training: “Why did we never learn how to treat ovarian insufficiency?” At the patients themselves: “Why didn’t he come see me earlier, when his diabetes was first diagnosed?” And again at the system: “Why do doctors leave out so much of the story when it comes to prevention, to patient power, to the autonomy we all have over our bodies and their health?” And to society at large: “Why is naturopathic medicine a last resort? Why is it expensive? Why are we seen as a last hope, when all but the patients’ hope remains?”

Insufficiency, of course, means things aren’t enough.

I feel powerless.

There is information out there. I put together a convincing plan for my patient with kidney failure. It will take a lot of work on his part. What will get us there is a commitment to health. It may not save his kidneys but he’ll be all the better for it. My hope starts to grow as I empower myself with information, studies some benevolent scientists have done on vitamin D and medicinal mushrooms. Bless them and their foresight.

As my hope grows, his must have faded, because he fails to show for the appointment. I feel angry, sad and slightly abandoned—we were supposed to heal together. Feelings of failure are sticky, of course, and I wonder what story took hold of him. was it one that ended with, “this is too hard?” or “there is no use?” or “listen to the doctors whose white coats convey a certainty that looks good on them?”

A friend once told me, the earlier someone rejects you, the less it says about you. I know he’s never met me and it’s not personal, but I take it personally anyways, just as I took it personally to research his case, working with a healing relationship that, for me, had been established since I entered his name in my calendar. In some way, like his kidneys, I’ve failed him. Since we’re all body parts anyways, how does one begin to trust another if his own organs start to shut down inside of him? Why would the organs in my body serve him any better than the failing ones in his?

I get honest with my patient whose ovaries are deemed insufficient (insufficient for what? We don’t exactly know). I tell her there aren’t a lot of clear solutions, that most of us don’t know what to do–in the conventional world, the answer lies mainly in estrogen replacement and preserving bone health. I tell her I don’t know what will happen, but I trust our medicine. I trust the herbs, the homeopathics, nutrition and the body’s healing processes. I admit my insufficiency as a doctor is no less than that of her ovaries, but I am willing to give her my knowledge if she is willing to head down this path to healing with me. Who knows what we’ll find, I tell her, it might be nothing. It might be something else.

It takes a brave patient to accept an invitation like the one above; she was offered a red pill or a blue pill and took a teaspoon of herbal tincture instead. I commend her for that.

There aren’t guarantees in medicine but we all want the illusion that there are. We all want to participate in the game of white coats and stethoscopes and believe these people have a godlike power contained in books that allows them to hover instruments over our bodies and make things alright again. Physicians lean over exposed abdomens, percussing, hemming and hawing and give us labels we don’t understand. The power of their words is enough to condemn us to lives without children, or days spent hooked up to dialysis machines. We all play into this illusory game. They tell us pills are enough… until they aren’t. This is the biggest farce of all.

I can’t participate in this facade, but I don’t want to rob my patient of the opportunity for a miracle, either. We share a moment in the humility of my honesty and admission of uncertainty. I know my patients pay me to say, “I can fix it.” I can try, but to assert that without any degree of humility would be a lie. How can one possibly heal in the presence of inauthenticity? How can one attempt to work with bodies if they don’t respect the uncertain, the unknown and the mysterious truths they contain? In healing there is always a tension between grasping hope and giving in to trust and honestly confessing the vulnerability of, “I don’t know.”

For my patient I also request some testing—one thing about spending time on patients’ cases and being medically trained is that you get access to information and the language to understand it. I notice holes in the process that slapped her with this life-changing diagnosis.

When her labs come back, we find she might not have ovarian insufficiency after all. Doorways to hope open up and lead us to rooms full of questions. There are pieces of the story that don’t yet fit the lab results. I give her a list of more tests to get and she thanks me. I haven’t fixed her yet, but I’ve given her hope soil in which to flower. I’ve sent her on a path to more investigations, to more answers. And, thanks to more information in the tests, I’ve freed her and her ovaries from the label of “failure” and “insufficient” and realized that, as a doctor, I can free myself of those labels too. The trick is in admitting, as the lab results have done in their honest simplicity, what we don’t know.

For the moment, admitting insufficiency might prove to be sufficient in the end.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Jun 9, 2015 | Art, Balance, doctor as teacher, Evidence Based Medicine, Medicine, Mind Body Medicine, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Patience, Patients, Philosophy

In most service industries, there are certain guarantees. If you go to a restaurant, your soup is guaranteed. At the GAP, you will get a pair of chinos, guaranteed. In lots of instances, you get what you are paying for and in most cases, you get to see if before you hand over your credit card—a coffee, a massage. In many cases, if you’re not satisfied, you can get your money back—guaranteed.

This is not the case in medicine. We cannot legally guarantee results. There are no guarantees.

Everybody and every body is different. Contrary to what it might seem like in our age of paralyzing fear of uncertainty, no one has all, or even most, of the answers.

Dr. Google makes it seem like we do, though.

When I see a new patient who is worried about their health and their future, I want to be able to promise them. I want nothing more than to say, “these breathing exercises will eliminate your anxiety, just like you asked for: poof! gone.”

I want to guarantee things.

I want to tell someone that, if they follow my instructions, they’ll never have another hypertensive emergency again. I want to, but I can’t. No one can. And our job is not to guarantee. It is to serve.

A $10,000 bag of chemotherapy pumped into your arm will not guarantee that the cancer goes into remission no matter how many studies show it has an effect. I can’t promise you’ll get pregnant, even though I’m doing my best, you’re doing your best and science is doing its best.

That’s all I can guarantee: that I will try my very best.

I can be your researcher, teasing out the useful scientific information from a sea of garbage and false promises—false guarantees from those who have no business guaranteeing anything. I can provide my knowledge, culminated from years of study and practice and life. I can sit with you while you cry and hear you share your story. I can let you go through your bag of supplements, bought in a whirlwind of desperation, and tell you what is actually happening in your body—something that doctor didn’t have time to explain. I have time to spend with you. We can have a real conversation about health. I can also make recommendations based on my clinical experience, research and millenia of healing practices. These recommendations will certainly help—virtually everyone sees some kind of benefit—but I can’t guarantee that either.

I watched a webinar on probiotics recently. The webinar sent me into a spiral of existential probiotic nothingness. I’ve been prescribing probiotics for years. I’ve seen benefits from them with my own eyes. Patients have reported great things after taking them and I feel better when I take them: my stomach gets flatter, things feel smoother, my mood gets lighter. Probiotics are wonderful. However, according to the research that was being presented by this professional, which he’d meticulously collected and organized, many things we thought about probiotics aren’t true. I’d have to change my whole approach when it came to probiotics, prescribing certain strains for certain conditions where they’d seen benefit. I remember feeling hard-done by by the supplement companies and the education I’d gotten at my school. How could we be so off base on this basic and common prescription?

At the same time, some skeptics were harassing me on Twitter, telling me that I’d wasted 4 years, that naturopathic medicine is useless and doesn’t help people. Besides having helped numerous people and having been healed myself, their words got to me. What if everything I know is as off-base as my previous knowledge on probiotics was?

The very next day, I called a patient to follow up with her. She’d kind of fallen off the radar for a while. She was happy to hear from me. I asked her how she was feeling, if she’d like to rebook. “I don’t need to rebook,” She told me, excitedly, “I’m completely better!”

After one appointment.

I was astounded and intrigued. Of course, we expect people to get better, but it takes time to heal, and I rarely go gung-ho on the first appointment, there was still lots left in my treatment plan for her. She’d been experiencing over seven years of digestive pain, debilitating fatigue, life-changing and waist-expanding cravings for sugar. It takes a while to reverse seven years of symptoms. It takes longer than a couple of weeks. But her symptoms were gone. She felt energized, her mood was great and she’d lost a bit of weight already. She no longer had cravings.

And she’d just started on one remedy.

Which was, you guess it, probiotics.

Sure, you might think. Maybe it wasn’t the probiotics, maybe she would have just gotten better on her own. Possible, but unlikely. She’d been suffering for years.

Ok, then, you say, maybe it was a placebo effect. Maybe it wasn’t the actual probiotics. Again, it’s possible. She’d tried other therapies before, which hadn’t worked, however and she “believed” in them just as much as the probiotic. And the probiotic made her better.

The point is this: we don’t know. Science is magical. People are magical. Medicine, which combines science with people, is the most magical of all. There are no guarantees.

The point is that anything can make anyone feel better: a good cry, a $10,000 bag of chemotherapy, journalling for 12 weeks or popping a probiotic. Some things have more research behind them. Some things we’ve studied and so we know some of the mechanisms for why things work. But we still have a lot of why’s and we always will. Everybody and every body is different. No two people or two conditions should receive the exact same protocol or supplement or IV bag or journalling exercise or cry-fest. We have no guarantees what will work or what will make you feel better. Just some research papers, some experience, maybe the odd dash of intuition or interpersonal connection and a firm resolve to want our patients to get better. And that’s a guarantee.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Mar 24, 2015 | Balance, Diet, Digestion, Docere, Education, Fitness, Food, Health, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles, Nutrition, Preventive Medicine

Many health complaints are common, but not normal.

Many health complaints are common, but not normal.

“I take migraine medicine everyday,” boasted L. She then went on to describe her plenitful medicine cabinet that, at the age of 23, she’d stocked quite well. “I get headaches when the weather’s bad, when I forget my glasses, when I’m hungry-” she went on. I repressed my immediate impulse to give her a list of supplements she could take and dietary changes she could make to never have another headache again, and simply said, “Well, L, you know I have a practice in the West end. If you want any more support…You can call—”

“—No, I’m good”, she responded, hurriedly. “I just need to find out how to get more of my medication.” The medication she referred to was high dose acetominophen, or Tylenol. She was taking 1 g pills and her doctor had told her that she could dose up to 4 g per day. Since 4 g will cause immediate liver failure, I was happy to learn she hadn’t needed to get that high… yet. What’s more, she wasn’t treating the cause of her condition. She was just addressing the symptoms, and consequently negatively affecting her health.

To use the car dashboard analogy, when your fuel light comes on and makes a noise while you’re driving on the highway, what do you do? Most people, without giving it another thought, will pull over to address the root cause of the chaos by adding more gas to the car. Very few of us will take out a hammer and smash the dashboard in. In fact, most of us cringe at how ridiculous the thought is. Imagine the entire naturopathic community cringing when they hear about someone swallowing several grams of Tylenol to smash out their migraine.

Pulling the car over to refuel and smashing the dashboard both serve to stop the annoying blinking and beeping of the fuel light. One of them is addressing the root cause and actually paying attention to what your car needs. The other is, well… I’ll let you come up with an appropriate adjective.

So this begs the question: why do we insist on smashing our symptoms away? The fuel light may be annoying, but drivers value its presence as a tool to let us know that we need to refuel lest we end up stranded on the highway without gas. The blinking light lets us know what is going on inside our car.

Why don’t we view our body’s symptoms in the same way?

I have patients who think that their depression is a part of them, or that the painful distention under their belly buttons after eating is “normal”. Sometimes we identify with our physical ailments to the point where they define us, as if it’s our lot in life to have acne or poor digestion or to be overweight—it’s not.

Dandruff, painful menses, seasonal allergies, aches and pains are not “normal.” Sure, they’re common. No, they don’t necessarily mean you have some life-threatening disease, and therefore your family doctor probably doesn’t have a reasonable solution for them, besides smashing at them with the hammers in their toolbox from time-to-time.

When I saw my first ND, I was excited at the idea that, even though my doctor assured me that the random, annoying symptoms I was suffering from were “normal”, they were in fact not normal and something could be done about them. From the ND’s standpoint, the symptoms were an indication of budding imbalances and treating them was preventing more serious conditions down the line. Feeling cold all the time and excessively full after meals weren’t just annoying symptoms, they were important messages from my body that things weren’t all right and that something needed to be done.

Is there an annoying symptom you’ve been experiencing that you’ve come to accept as something you just have to live with?

Contact me to find out what we can do about it!

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Feb 2, 2015 | Love, Mental Health, Naturopathic Philosophy, Relationships

My classmate, A, has a treatment plan for me. He wants me to exercise—not the light walks I’ve been doing, but intense cardio intervals and weight-lifting. He wants me to get more sleep and drink more water. When he gives me the instructions, I feel slightly disappointed; I could have prescribed this plan to myself. In fact, even in telling him the story about my fatigue, I had already predicted what he’d recommend. I could hear myself admitting to not getting enough sleep and to often forgetting to drink water. I just hadn’t thought consciously about those facts for a while. Life and self-deception had kind of gotten in the way.

My classmate, A, has a treatment plan for me. He wants me to exercise—not the light walks I’ve been doing, but intense cardio intervals and weight-lifting. He wants me to get more sleep and drink more water. When he gives me the instructions, I feel slightly disappointed; I could have prescribed this plan to myself. In fact, even in telling him the story about my fatigue, I had already predicted what he’d recommend. I could hear myself admitting to not getting enough sleep and to often forgetting to drink water. I just hadn’t thought consciously about those facts for a while. Life and self-deception had kind of gotten in the way.

In one way, because I had the answer in front of me, and in another way to please A, who I’d have to report back to the following week, I started to exercise. When I got home, I stopped telling myself that a short, light walk would be enough—I had to start sweating. I stopped kidding myself that five hours of sleep a night was enough and that watching TV on my laptop while lying in bed was a substitute for rest. I made the changes and I began to feel better.

I might have had the internal fortitude to do all of this on my own, but it was talking to someone I trusted that gave me the push I needed. I saw my issues and current lifestyle reflected in A’s eyes. The mirror he held up to me gave me the jolt required for me to start taking care of myself.

The healing relationship is something that is not often credited in mainstream medicine. I am taking a course in Motivational Interviewing (MI) in which we learn to tailor our patient interactions to inspire patients towards making healthy changes in their lives. MI helps people move past places of ambivalence because it acknowledges that, while patients have the power and authority to make changes, they also need the therapeutic relationship to start the first steps of change. We’re often told to share our goals with a friend. One reason for this is that we are held accountable. Another reason is that saying the words out loud helps solidify the need to make a change. Telling another person mirrors our needs, wants and ambitions back to us. Through the act of sharing we gain mutual support and are more likely to move forward with our goals.

When I ended a 5-year relationship and entered the dating scene in late winter of last year, I often joked to my friends that dating was “free therapy.” I had to push myself to leave my bubble of comfort and sit across from a stranger. I had to risk being evaluated by someone else. Dating showed me the need to take chances with my heart and express my feelings and vulnerability. I was confronted by my insecurities—feelings of unworthiness, worry that I wasn’t attractive enough and a deep-rooted fear of rejection and abandonment. I was forced to stare these fears down, acknowledge their existence and work to move past them. This experience helped me become a better person and a better doctor, improving the relationships I have with my patients and coworkers.

Relationships expose our wounds. After all, the human experience is formed in relationship. Even withdrawn introverts rely on others for their daily experiences. Hermits living in the woods are reliant on relationships, or lack thereof. Their identity, forged by their need to escape from others through the conscious rejection of relationships, still reflects their intersubjectivity. Our earliest relationships establish our deeply held beliefs about ourselves and the world. Everything we learn about ourselves is through relationships with other people.

I read this wonderful quote in an article recently,

“Our wounds were formed in-relationship and can only be healed in-relationship. No amount of meditation on a mountain can solve your mommy issues.”

Healing, whether physical, mental, emotional or spiritual, must be done through interpersonal connection. Relationships help expose our wounds while showing us what we can do to address them. While we ultimately heal ourselves, we intuit that the healing process needs the hands of another. Through my last relationship I’ve seen my insecurities held up in front of my face. The need for developing my sense of self-worth, self-love and self-acceptance began to cry out loudly, when reflected through the prism of the relationship I was in. When we’re alone it is easy to ignore these callings—there is no one beside us, challenging us to evolve, and it becomes easier to settle into our ways.

Self-work cannot be done alone.

Healing requires reflection, mirroring, empathy, storying, support and, sometimes, accountability. It requires more than just expertise, self-will and determination. When working on ourselves interpersonally, we are forced to see ourselves through the eyes of another human being and develop the darkest, hidden parts of ourselves, becoming whole.

Therefore, true healing cannot be done outside of relationship. We need someone to share and rewrite our stories with. In some cases, it can be a partner, family member or friend. In others, the ears, eyes and hands of a trusted professional can help you move to the next level of conscious healing and self-evolution.

In short, Googling your symptoms can’t heal you.

I love this quote from Julie Delpy’s character in the movie Before Sunrise:

“If there’s any kind of magic in this world it must be in the attempt of understanding someone sharing something. It’s almost impossible to succeed, really, but who cares? The answer must be in the attempt.”

Healing is in the attempt.

by Dr. Talia Marcheggiani, ND | Nov 7, 2014 | Medicine, Naturopathic Philosophy, Naturopathic Principles

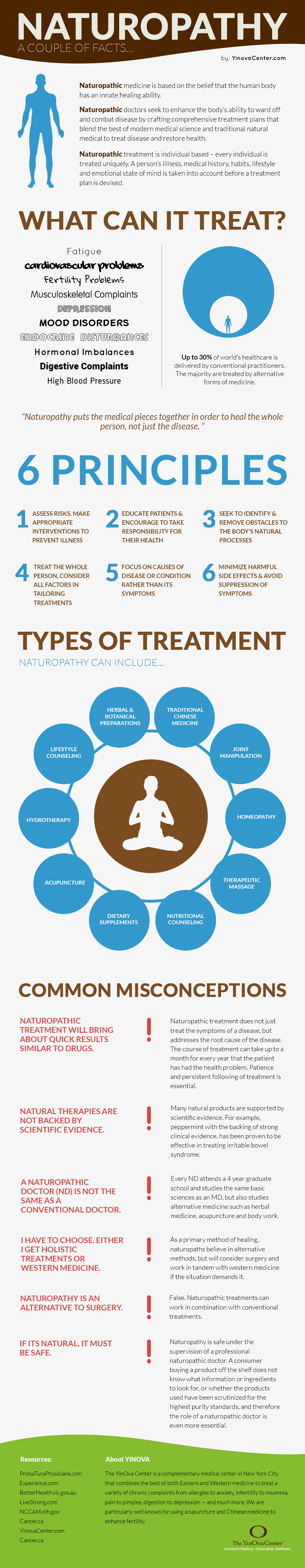

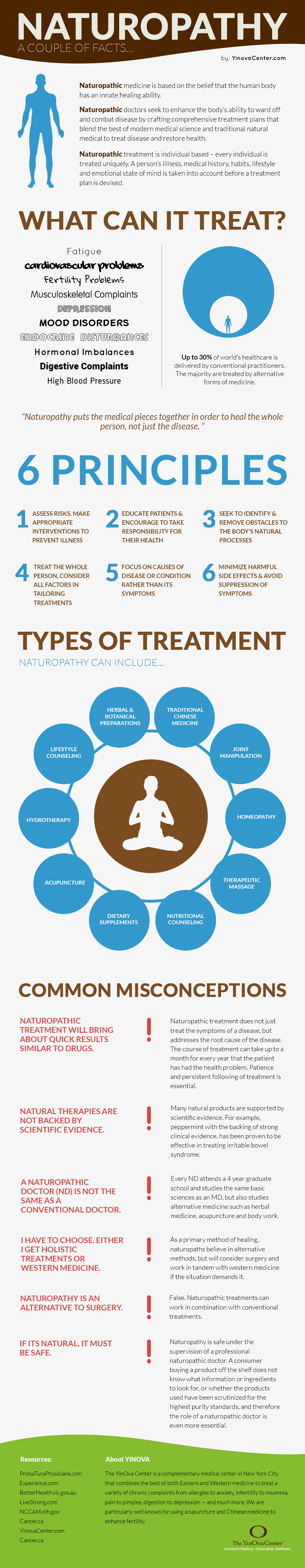

Do you love and believe in naturopathic medicine but feel at a loss to describe it to your family and friends? Despair no more. Those at the YinOva Center in New York have created a cool infographic about naturopathic medicine, which “Alex” was kind enough to share with me. Take a read and feel free to pass it on!

People seek out naturopathic doctors for expert advice. This immediately positions us as experts in the context of the therapeutic relationship, establishing a power imbalance right from the first encounter. If left unchecked, this power imbalance will result in the knowledge and experience of the practitioner being preferred to the knowledge, experience, skills and values of the people who seek naturopathic care.

People seek out naturopathic doctors for expert advice. This immediately positions us as experts in the context of the therapeutic relationship, establishing a power imbalance right from the first encounter. If left unchecked, this power imbalance will result in the knowledge and experience of the practitioner being preferred to the knowledge, experience, skills and values of the people who seek naturopathic care.